Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Late-Onset Spinal Cord Injury: Rehabilitation Considerations for the Older Adult Experiencing SCI, presented by Kevin Cezat, PT, DPT, GCS, RAC-CT, and Kristen Cezat, PT, DPT, NCS, ATP/SMS.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to recall the incidence and common causes of late-onset spinal cord injury (SCI) in older adults.

- After this course, participants will be able to explain three normal age-related physiological and psychosocial factors influencing rehabilitation outcomes in older adults with SCI.

- After this course, participants will be able to discuss two age-related considerations for mobility interventions for older adults experiencing a late-onset SCI.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify and describe common types of wheelchairs that best support the functional and medical needs of older adults with late-onset SCI.

Introduction

Kristen: Kevin and I share the same last name because we’re married. We’re both excited to bring this topic to you today since it connects directly to the work we’ve each been committed to throughout our careers. My specialty has always been spinal cord injury, while Kevin’s focus has been geriatric rehabilitation. What makes today especially meaningful is that we can combine those two worlds, exploring their overlap and connections.

This topic is fun and essential because it highlights how much these areas of practice can inform one another. We’ll explain why this matters, draw on our experiences, and give concrete examples of how it plays out in practice.

Aging U.S. Population

When we look at the aging in the U.S. population in 2020, about one in six people was over the age of 65. That number continues to grow, and it represents the fastest-growing population in the United States. But this isn’t just a U.S. issue—it’s a global conversation. In fact, the United States ranked 34th worldwide in terms of aging populations and the proportion of older adults.

Because of that, we’re not just looking at this from a national lens; the literature reflects a global dialogue about aging, and that’s what we’ll be digging into together today. Specifically, when we consider individuals aged 65 and older who are living with spinal cord injury, we see that this is the fastest-growing group within the SCI population. That brings with it many unique considerations, challenges, and opportunities, which will shape much of our conversation today.

Aging and SCI

We want to begin by distinguishing important aging areas concerning spinal cord injury. Often, you’ll see two different concepts discussed in the literature. The first is early-onset spinal cord injury, which refers to someone who experiences a spinal cord injury at a younger age and then continues to age while living with that injury. The second is late-onset spinal cord injury, which refers to individuals who are older adults when they sustain their spinal cord injury.

The literature is somewhat ambiguous about how these categories are defined. Different studies use different age cutoffs, and the definition of “older adult” varies depending on the source. You’ll hear us reference this lack of consistency throughout our discussion because it influences how research findings are interpreted and applied.

For today’s conversation, our focus is on late-onset spinal cord injury. We will not be addressing those who sustained an injury earlier in life and are now aging; instead, we are concentrating only on individuals who sustain a spinal cord injury as older adults.

What's the Big Deal?

So what’s the big deal? When someone experiences a spinal cord injury later in life, their needs and outcomes look very different from those who sustain an injury at a younger age. Unique and complex considerations come into play when an older adult experiences an SCI. We know that older adults respond differently to trauma, and they have different physiologic reserves compared to younger individuals, and that difference directly impacts both recovery and long-term outcomes.

Kevin will go into more detail on this when he discusses normal versus abnormal aging in older adults, but it’s important to highlight how much these factors matter. Responses to trauma, reduced physiologic reserves, premorbid frailty, multiple comorbidities, and the influence of medications all play significant roles in shaping the course of recovery. These are areas where the literature gives us important insights and where practice requires careful attention.

Once again, we return to the ongoing debate about age itself. The definition of “older adult” remains controversial across studies, complicating how we interpret and apply findings to practice. That variability is part of what makes this conversation both challenging and essential.

Traumatic SCI Incidence

I always like to start with a brief snapshot of the incidence and epidemiology of spinal cord injury before diving deeper into the conversation. Clinically, we know what we see day to day, but it’s just as important to step back and understand the bigger picture of what’s happening across the country. Kevin and I feel incredibly fortunate in our careers to have regular contact and interaction with therapists from all over the United States in our respective specialties. That perspective is invaluable, but I also rely heavily on the literature because I want to know—are the patterns I’m seeing in my practice unusual or unique, or are they consistent with national trends and the broader epidemiological data?

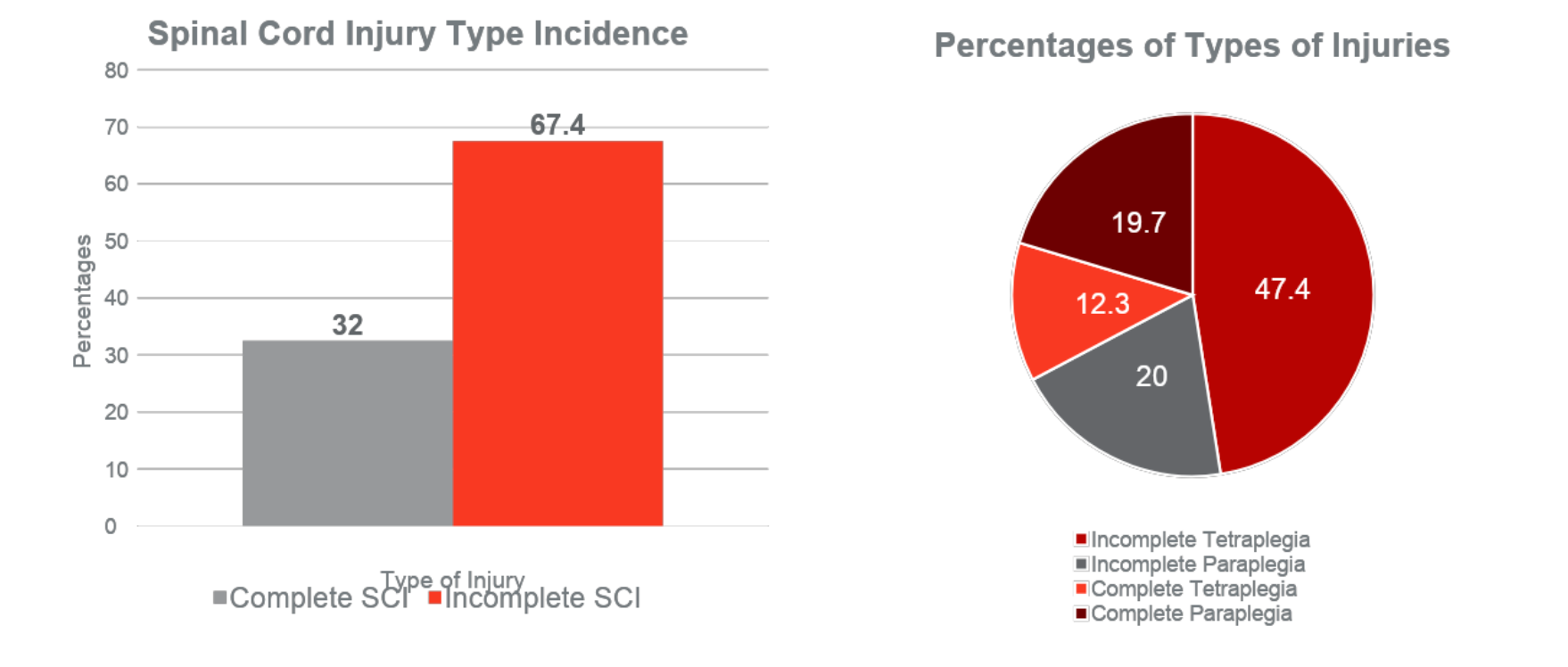

That’s why I find it so important to review these statistics, as seen in Figure 1. They give us a foundation and help frame the discussion. So here, we’re looking at the national averages for traumatic spinal cord injury incidence, which provide a context for understanding not only what’s happening locally in our caseloads, but also how those experiences align with what’s being seen across the country.

Figure 1. SCI Incidence and types of injuries. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

That distinction is important because while there are other types of spinal cord injury, such as non-traumatic injuries, we don’t have the same quality or robustness of data for those populations. Some datasets are available, but they’re nowhere near as comprehensive as what we have for traumatic injuries. So for this discussion, we’re focusing specifically on traumatic spinal cord injuries.

Looking at the most recent numbers from 2024, about 67% of individuals who sustained a spinal cord injury had an incomplete injury, while about 32% had a complete injury. Within those categories, the largest group—nearly half—experienced incomplete tetraplegia. That means the cervical spine was involved, resulting in impairment across all four limbs. The distribution shifts into other classifications from there, but this remains the most common presentation.

This perspective is essential because it helps us anticipate what we will most likely encounter in clinical practice. Understanding the national trends allows us to align what we see in our caseloads with what’s happening across the broader population.

Types of Spinal Cord Injury

The International Standards for Neurologic Classification of Spinal Cord Injury is one of the primary outcome measures we use clinically to determine the level and type of injury. It continues to be considered the gold standard worldwide for identifying the extent of spinal cord injury. Of course, imaging and other diagnostic tools are also part of the overall assessment. Still, at the bedside and in rehabilitation clinics across the globe, this is the tool we rely on.

Within this framework, the ASIA Impairment Scale helps us classify injuries by breaking them into five categories based on motor and sensory assessment. Individuals with an ASIA A classification have no motor or sensory function below the level of their injury, which means they are considered motor and sensory complete. ASIA B represents a sensory incomplete injury—there is some preserved sensation below the injury level, but no motor function. Although weak, ASIA C is where motor function emerges, with most muscles graded three or lower. ASIA D is also motor incomplete, but over half of the key muscles below the injury grade at three or higher show a stronger presentation. Finally, there is an ASIA E classification, which is extremely rare. I’ve personally only seen one in my entire career. That is when someone sustains a documented spinal cord injury but regains normal motor and sensory function.

Understanding this classification system helps us describe and predict the clinical presentation and frames how we think about outcomes and interventions. This connects directly to the next part of our discussion: fall risk. We want to think about falls in terms of prevention—avoiding new spinal cord injuries in older adults—and intervention, where our recommendations for function and safety after these classifications and the level of residual ability shape SCI. Kevin will be taking a closer look at those factors shortly.

Causes of SCI of the Older Adult

There are some essential differences in the causes and mechanisms of spinal cord injury when we compare older adults to younger populations. For individuals over the age of 65, falls are currently the leading cause of traumatic spinal cord injury. In contrast, motor vehicle accidents remain the most common cause for younger adults. While we still see motor vehicle incidents contributing significantly to SCI in older adults, falls stand out as the primary driver in this age group.

When we shift to non-traumatic spinal cord injuries, the picture looks different again. In older adults, common causes include surgical intervention complications, neoplasms or cancers, tumors, and infections. Each of these etiologies brings medical and functional considerations, which influence how we approach rehabilitation. Recognizing these distinctions is key to understanding the most common presentations of SCI in older adults and tailoring interventions appropriately.

Common Presentation for Older Adults With SCI

Older adults are more likely to experience incomplete tetraplegia, and this aligns with what we already know from national data—that incomplete tetraplegia is the most common overall presentation of spinal cord injury. In older adults, the proportion is even higher, with a large number of injuries occurring at the cervical level and presenting incompletely. This means there is typically some preserved movement or sensation below the injury.

One condition that frequently appears in both the literature and clinical practice is central cord syndrome. This is the most common type of incomplete spinal cord injury in older adults. For those less familiar, central cord syndrome is characterized by greater paralysis or weakness in the upper extremities than in the lower extremities. It often occurs in individuals over the age of 50 as a result of hyperextension injuries—something we see frequently with falls, where an older adult may hit their head, or in motor vehicle accidents. Age-related narrowing of the spinal canal also contributes, making this population more susceptible.

Without going into the full details of spinal cord anatomy, what’s essentially happening is compression or squeezing of the spinal cord in its central region, where motor function for the upper extremities is located. As a result, we see more impairment in the arms than in the legs. Of course, spinal cord injury presents in many different ways, and no two cases are identical. Still, central cord syndrome is a pattern we often encounter in older adults, both in research findings and day-to-day practice.

Physiological and Psychosocial Changes with Normal Aging

Kevin: This section is structured around separating normal aging from abnormal aging, the impact these processes have on our clients, and the key considerations we need to keep in mind from a therapy perspective. Before we get into that, I’ll briefly review my background so you have some context for where my comments are coming from.

For the past 15 years, I’ve worked almost exclusively in long-term care, with much of that time spent in CCRC Life Plan communities. These environments provide a unique window into the aging process, since they typically include independent living, outpatient services from within and outside the community, home health, assisted living, skilled nursing, and often a memory care unit. That’s been the foundation of my work until the last two to three years, when I transitioned into a broader clinical quality role. In this role, I’ve had the opportunity to look across a broader range of long-term care providers, from rural to urban settings, including everything from standalone skilled nursing facilities to full-scale life plan communities.

For many geriatric professionals, spinal cord injury is one of the more intimidating populations to manage, particularly acute injuries in older adults. As we’ll see, the older adult population is already highly complex, and layering on a complex and dynamic condition like SCI adds even more challenges. It can feel overwhelming to account for every possible factor, and the reality is that we often don’t have time to address them all. However, having a clear vision of the landscape and focusing on key priorities helps guide effective intervention.

On a more personal note, I also have some family experience with spinal cord injury, though non-traumatic. My father, my uncle, and my paternal grandmother all experienced spinal cord injuries of different types. That personal exposure has given me another perspective on how these conditions impact individuals and families beyond the clinical setting.

Normal Aging Vs. Disease

So what exactly is normal aging versus abnormal aging? We all know that as we grow older, our bodies undergo various changes across different systems. The challenge, however, is that there isn’t a single, universally accepted definition of normal aging or the precise point at which it crosses over into disease or pathology. There are common themes that appear consistently in the literature, but the details shift depending on the model you’re looking at.

For us in clinical practice, being able to recognize the difference is essential. It helps us know when we are looking at expected, age-related change and when we are dealing with a pathological process that requires intervention, further testing, or a different care plan. Of course, that doesn’t mean preventative strategies and proactive interventions aren’t valuable during normal aging—but the approach changes significantly when something falls into the disease category.

What makes this tricky is that a mix of factors influences normal aging. There are genetic variables, but the research increasingly shows that lifestyle and environmental factors account for a significant portion of the changes we see with aging. That’s both exciting and challenging. It’s exciting because many of those factors are modifiable. It’s difficult because it forces us to determine our priorities in supporting healthy aging for our patient populations.

Normal aging is described as gradual and symmetrical, and most importantly, it does not typically result in significant impairment in function. That functional distinction is the marker most often used to draw the line between what is considered normal aging and what is considered abnormal or pathological aging. At the same time, we know that certain medical conditions become more prevalent as people age, but their prevalence does not automatically make them part of normal aging. They are simply conditions we encounter more frequently in older populations.

Generational Differences and Health Literacy

Since we’re breaking down older adults into generational differences, it’s worth considering how each group interacts with the healthcare system. This is especially relevant when we think about the person-centered care model, because how individuals engage with providers, technology, and medical decision-making can vary greatly depending on the generation.

Traditionally, we consider the breakpoint for older adulthood around age 65. Using that standard, most of our current older adults are from the Silent Generation and the Baby Boomers, with a small number of the Greatest Generation still with us. The Greatest Generation, born before 1928, is now 97 and older, and while less common, they remain part of our clinical populations. The Silent Generation, born between 1928 and 1945, is in their late 70s to 90s, making up a significant share of today’s older adult group. Baby Boomers, born between 1946 and 1964, are now 61 to 79, and they are actively moving into the older adult category. Within the next five years, the entire Baby Boomer generation will be over 65. Following close behind will be Generation X, which will introduce yet another layer of generational differences to consider.

These distinctions matter because each generation brings its tendencies. We see predictable variations, such as differences in comfort with technology, since many older adults did not grow up using it. But beyond technology, there are more profound differences in how people interact with healthcare systems. Some generations place strong inherent trust in authority figures, while others are more skeptical, shaping how they perceive medical advice and care.

A story my wife often shares illustrates this well. Her grandfather, a military veteran and engineer, was brilliant and engaged with technology in his way. Toward the end of his life, he was in and out of the hospital. When we asked him how things were going and what he thought of the physicians, he replied that the doctors “had no idea what was going on” and “didn’t know a thing about him.” At first, that didn’t make sense, because we knew the physicians and trusted their competence. But when we pressed further, he explained that none carried his chart into the room. For decades, his primary care physician always came in with the chart, reviewed results and notes from previous visits right before him, and then discussed the plan. With the transition to electronic medical records, doctors were now reviewing everything outside the room before entering. For him, the absence of a physical chart meant the doctors were essentially guessing. Even though he was intelligent and not unfamiliar with technology, this shift changed his trust in his physicians and colored his entire experience of the healthcare system.

These generational and experiential differences affect how older adults engage with care, highlighting the importance of tailoring our approach. Health literacy adds another layer. While many older adults are well-educated, health literacy is defined differently—it’s about the ability to find, understand, and evaluate health information to make informed decisions. In this regard, most older adults are not considered health literate. Only about 3% are classified as fully health literate. Given the complexity of healthcare—and the additional jargon that comes with something like spinal cord injury—it becomes even harder for older adults to interpret and act on medical instructions. Many of us see this firsthand with our parents. It’s often necessary to send a second person to medical appointments, because otherwise they may leave with a completely different understanding of what was discussed, all because of a few unfamiliar abbreviations or terms. This reality makes it clear that generational context, communication strategies, and health literacy must be front and center in our care for older adults.

Generational and Literacy Considerations

When it comes to strategies, we won’t go into all the fine details of generational differences since that’s already well-studied, but it’s worth emphasizing a few key points. Suppose you work with a particular population group. In that case, it’s essential to take the time to do some research and consider your audience—how they typically like to interact, what methods of communication resonate most with them, and what barriers may exist. Using a variety of mediums is helpful, such as giving verbal instructions and providing printed materials that are adjusted to appropriate health literacy levels. These adjustments can significantly affect whether information is understood and applied.

A simple yet often overlooked approach is asking the patient how they prefer to receive information. Starting with their preferences creates a stronger therapeutic alliance and ensures the strategies you use are patient-centered. Pacing is another critical piece with older adults, in particular. As Kristen and I both know, we tend to talk quickly when presenting or teaching, but with patients, it’s essential to slow down, speak at a measured pace, and allow time for processing.

Engagement is the cornerstone. Asking patients how they’d like to communicate, involving them directly in care planning, and practicing shared decision-making fosters trust and adherence. These small adjustments in approach can make a meaningful difference in outcomes and the patient’s overall experience with the healthcare system.

Understand the Patient's Living Environment

Older adults live in various living situations, and these arrangements can become especially complicated as people age. About half of older adults live with family members—this might mean adult children, siblings, or other relatives. Around 40% live alone, though that can take many forms: private homes, condos, apartments, or even assisted or independent living communities. Of course, “living alone” for an older adult can look very different depending on the type of setting and the amount of informal support available. About 8% live in long-term care facilities such as skilled nursing or memory care units.

Each of these settings comes with unique considerations, which directly affect intervention planning, patient education, and discharge recommendations. For individuals with SCI, the environment often adds extra layers of complexity. For example, many assisted and independent living facilities have strict policies about what equipment can be used, the amount of assistance staff are permitted to provide, and the level of independence required to remain there. Skilled nursing facilities sometimes restrict the use of power wheelchairs under certain circumstances, often citing safety concerns. While understandable, this can quickly become complicated when the goal is to maximize a person’s independence.

So while the discharge setting is always essential for any patient, it becomes particularly challenging for older adults. Their living arrangements often represent a patchwork of support structures, and when spinal cord injury is added into the picture, the layers of complexity only multiply.

Social Determinants of Health for Older Adults

When we look at older adults, social determinants of health play a significant role in shaping outcomes. By definition, these are the conditions in which people are born, live, and work—factors that ultimately influence health in both direct and indirect ways. Over the years, we’ve better understood how these factors affect risk, recovery, and overall well-being, even when the connections are more correlational than causal. They’re becoming increasingly helpful in stratifying risk and shaping care plans.

In long-term care, there has been a push to gather more structured data on social determinants of health to guide decision-making and planning. At the same time, it has entered the political sphere, and there’s still debate over how best to collect, use, and regulate that information. It’s an evolving area that will likely shape the future of care in meaningful ways.

Breaking this down into demographics, marital status is one crucial factor. Just over half of older adults are married, about a quarter are widowed, roughly 13% are divorced or separated, and only about 6–7% have never been married. These numbers will likely shift in the coming years as generational demographics change, but even now, marital status is highly indicative of health outcomes. Strong social connections can be protective, while lacking support can complicate recovery and discharge planning.

Socioeconomic level is another crucial consideration. In my own experience, I’ve worked at both ends of the spectrum—high-income individuals in life plan communities and those with minimal means in other facilities. Kristen’s hospital-based experience has primarily been with patients on the lower end of socioeconomic standing. These differences matter because they directly influence discharge options, access to equipment, and the ability to manage health independently at home. National data shows that about 10% of adults over 65 live in poverty, and about one-third are considered low-income. That means over 40% of older adults may be unable to afford essential items such as wheelchairs, catheters, medications, or home modifications without financial assistance. These are often the very things that prevent complications like pressure injuries or infections.

On the other hand, the majority of older adults are insured, primarily through Medicare. Most are enrolled in traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage, and some qualify as dual enrollees with Medicaid. That coverage generally ensures access to acute care and some rehabilitation—whether in skilled nursing facilities or inpatient rehab. Medicare typically allows up to 100 days in a skilled nursing setting, for example, but it does not cover long-term care. Neither Medicare nor Medicare Advantage plans usually pay for ongoing custodial care in a facility once rehabilitation goals have plateaued. That gap between coverage and need is one of the biggest challenges in discharge planning for older adults with spinal cord injury.

Cognition and Aging

Now I want to shift into what I think is the biggest X factor in all of this—the piece that complicates everything more than anything else—and that’s cognition. You can be as well prepared as possible, with a structured approach and a solid didactic understanding. Still, cognition is the variable that forces you to be dynamic, creative, and adaptive in the way you develop and carry out a plan of care.

Cognitive status truly changes everything. It influences how patients engage with therapy, follow through with recommendations, and even how safe or feasible specific interventions become. We’ll get into more detail about the “why” behind this a little later. Right now, it’s important to recognize that cognition is the factor that can completely shift the trajectory of care for older adults with spinal cord injury.

Cognitive Deficits

As you would expect, cognitive changes are widespread with aging. About two-thirds of individuals in the United States will experience some form of cognitive impairment during their lifetime. When we narrow that down to the long-term care setting, roughly half of nursing home residents are living with Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia.

This prevalence has massive implications for everything we do. It shapes participation in therapy, impacts decision-making, alters safety considerations, and influences how we communicate with patients and families. We don’t need to get lost in the statistics to appreciate the weight of it—most of us see this every day in practice and understand how central cognition is to shaping outcomes for older adults.

Normal vs. Abnormal?

So the question becomes: when does aging shift from normal to abnormal? There isn’t a perfect cut point or universal standard that everyone agrees on. While we expect some changes to the brain just as we do with other body systems, it can be difficult to clearly define where normal aging ends and pathology begins.

Generally, the changes we anticipate with normal aging include slower conceptual reasoning—things like problem-solving or managing abstract concepts—slower processing speed and reaction time, and mild lapses in declarative memory. These are the “tip of the tongue” moments, forgetting a recent fact or a name, or taking longer to recall details. Most of us have seen our grandparents or parents go through some of these shifts, and while frustrating, they’re expected parts of aging.

Abnormal changes, however, go beyond that. Severe memory loss—forgetting the names of close family members or significant life events—falls into this category. So, there are significant difficulties with language, whether in understanding, expressing, or processing. Executive dysfunction—trouble planning, organizing, or making decisions—also signals abnormal change, as do personality and behavioral shifts. These sudden changes in mood, social behavior, or emotional regulation are often especially concerning. Finally, getting lost in familiar places is another hallmark sign of pathology. These changes are not typical aging but rather the result of underlying conditions.

The causes are numerous. Neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s are common contributors. Vascular events and structural brain changes also play a role, as do traumatic injuries or tumors. And one of the most important, often overlooked, factors is delirium.

Delirium is something every clinician working with older adults needs to understand. It’s a sudden, typically transient alteration in brain function—meaning it’s not permanent, but it does represent a significant change from baseline. The causes are varied, but among older adults, the most common is infection, particularly urinary tract infections. Often, the only sign of a UTI in an older adult may be a sudden change in mental status. Other triggers include medications and anesthesia, as older adults are much more sensitive to drugs and metabolize them more slowly. Substance use disorders, dehydration, and malnutrition are also common contributors. About 40% of community-dwelling older adults are considered chronically dehydrated, and roughly one in four have nutritional deficits or altered intake patterns.

The key takeaway for clinicians is that we must be vigilant. Recognizing delirium quickly—whether the sudden change appears over a day or even within hours—allows us to mobilize the interdisciplinary team and identify the underlying cause. Is it an infection? A medication interaction? Dehydration? Catching these changes early is critical for preventing secondary complications such as falls, hospitalizations, and further cognitive decline.

Cognition and Aging Considerations

There are a wide range of tools available to help identify and stage cognitive changes in older adults, and these can be used not only by physical therapists but also by other members of the interdisciplinary team. Screening tools are designed to detect whether there’s a change—such as mild cognitive impairment—while staging tools are used once a condition like dementia is already established, to determine where someone falls along the spectrum. That information is critical for guiding decisions about care, such as whether someone can safely live alone, requires 24-hour support, or can still learn new tasks. Even if you’re not entirely comfortable using all of these tools, relying on your IDT colleagues to administer them and understanding what the results mean for your care plan is essential.

Another critical point is how cognitive status, even in normal aging, complicates the use of clinical practice guidelines. I strongly advocate for guidelines and hope to see more developed in the future. Still, one challenge in long-term care is that older adults—especially those with cognitive impairment—are often excluded from the research that informs these guidelines. That means the very population we treat most frequently isn’t represented in the data. The takeaway isn’t that guidelines aren’t useful—they are—but that we need to apply them thoughtfully, recognizing when modifications may be necessary because our patients don’t fit the populations on which the recommendations were built.

Cognition also complicates objective testing. Many patients can’t follow multistep commands, which makes certain outcome measures invalid. Others may not respond reliably to cues. That limitation affects not just testing, but also intervention planning. For example, if someone cannot follow directions consistently, we must adapt interventions to ensure they’re still safe and effective. Durable medical equipment prescription is another area where cognition matters—if someone can’t safely learn to use a device, do we adjust the recommendation, bring in caregiver training, or find a simpler alternative?

Even dosing becomes more challenging when patients can’t provide reliable feedback on perceived exertion or symptom intensity. In those cases, we’re left relying more heavily on clinical observation. And education has to be tailored carefully. Suppose an individual is below the threshold for new learning. In that case, our focus may need to shift toward caregiver education, ensuring someone else has the knowledge and skills to manage the equipment, safety strategies, and daily care.

In all of these areas, cognition forces us to adapt. It doesn’t mean our care is less effective, but it does mean our approach has to be more flexible, individualized, and inclusive of support systems around the patient.

Polypharmacy With Aging

Cognitive impairment is one critical factor, but another equally important consideration with older adults is polypharmacy. By definition, polypharmacy is the regular use of five or more medications. Unfortunately, this isn’t the exception for older adults—it’s the norm. The average adult over 65 takes between 15 and 18 prescriptions per year, far exceeding that threshold. In skilled nursing facilities, polypharmacy is almost universal, with estimates as high as 80–90% of residents on five or more medications. Even in community-dwelling older adults, it’s still extremely common.

This widespread medication use is linked to a host of issues, not just because of the sheer number of prescriptions, but also because older adults process drugs differently and are more sensitive to side effects. For us in therapy, the timing of medications is a key consideration. For example, we may want to schedule sessions to align with Parkinson’s medications or pain medications to optimize participation and mobility. On the other hand, some medicines may cause dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, or other side effects that make therapy less safe if scheduled too closely.

Awareness of medication impacts also extends to monitoring vital signs and recognizing early warning signs. A good example is with beta blockers. Many older adults take these, but we cannot rely on heart rate as a measure of exercise intensity because they blunt the heart rate response. In those cases, we must adjust our dosing methods and use alternative monitoring strategies.

While we’re not pharmacists, therapists are often on the front lines of observing how medications affect function, participation, and safety. That means we need to be informed and proactive in our role. Some excellent resources are worth noting: the Beers Criteria, which provides an updated list of medications that are either high risk or contraindicated in older adults; and the START and STOPP tools, which offer structured guidance for initiating or discontinuing medications safely in this population. These tools help us understand where potential problems may lie and give us the language to collaborate effectively with physicians, pharmacists, and the rest of the healthcare team.

Genitourinary and Gastrointestinal System in Aging

Let's go into general urinary and GI system changes in older adults.

Genitourinary Changes in Older Adults

Many of these age-related changes aren’t surprising, but they’re essential to keep in mind, especially when layered on top of spinal cord injury. Older adults often experience reduced bladder capacity and weakened pelvic floor or bladder muscles, which affect continence and increase the likelihood of complications. Kidney function naturally declines with age as well, which raises the risk of chronic kidney disease. This adds another layer of concern for individuals with complex medical needs.

For men, prostate enlargement is a common issue that can significantly complicate bladder management. When intermittent catheterization is required, for example, prostate changes can make the process more difficult and increase the risk of urinary retention, infection, or trauma. While common in older adults, these urologic challenges take on even greater significance in the context of SCI, where bladder health is already a central part of long-term management and quality of life.

Genitourinary Considerations

In patients with SCI, it’s essential not to view incontinence management as simply placing someone on a toileting program. If that’s the only tool in your toolkit, then it’s time to expand your approach. Building a structured set of resources, assessment tools, and practical guides will give you a more comprehensive framework to evaluate, manage, and educate about incontinence.

This is an area where we as therapists can play a significant role. Incontinence is already prevalent in older adults, and in SCI, it becomes even more complex. We need to be comfortable identifying different management options, monitoring closely for UTIs, and recognizing the ripple effects on skin integrity. Incontinence-associated dermatitis is one example, but we also see increased vulnerability to pressure injuries and infection when bladder and bowel issues aren’t well controlled.

Another critical point is the relationship between incontinence and falls. In long-term care, bathroom-related issues are one of the primary drivers of fall incidents. When incontinence isn’t managed well, patients may rush, take risks, or attempt unsafe transfers to get to the bathroom in time, all elevating fall rates. Addressing incontinence effectively isn’t just about dignity and comfort—it’s also a key factor in safety and overall outcomes.

Gastrointestinal Changes in Older Adults

When we shift to the gastrointestinal system, several changes become common in older adults, and these can have a major impact when combined with spinal cord injury. Slowed digestion and reduced peristalsis increase the likelihood of constipation, while changes in swallowing function raise the risk of dysphagia. Nutrient absorption is often impaired, contributing to malnutrition or deficiencies over time.

Taste is another factor. With age, there’s often a significant loss of taste buds, and many older adults compensate by heavily seasoning food—often with salt. That creates complications, particularly in individuals with kidney dysfunction or cardiovascular conditions. Beyond this, we also see notable changes in the gut microbiome with age, which can contribute to digestive difficulties and further complicate overall GI health.

Together, these changes increase the risk for conditions such as GERD, chronic constipation, and dysphagia. These affect comfort and nutrition and play into broader issues like energy levels, participation in therapy, and long-term quality of life.

Gastrointestinal Considerations

From a therapy perspective, one of the most significant responsibilities is to stay alert to red flags, particularly medication-related ones. Older adults are far more likely to experience side effects, and recognizing and educating patients about these risks is critical. Even if we don’t always have the time to dive deeply into pharmacology during sessions, having a working understanding of how medications interact with both geriatric and SCI-specific issues is part of providing safe care.

Diet education is another area where therapists should have at least a foundational level of knowledge. Nutrition becomes complicated when you factor in the general challenges of aging and the specific complications of SCI. For example, increasing fiber intake is often recommended for older adults, but in some cases, it can worsen symptoms if not monitored carefully. Balancing those nuances requires close observation and, ideally, collaboration with dietitians.

In addition, we know older adults are at higher risk for malnutrition and dehydration, which further complicates care and can magnify issues like skin breakdown, infection risk, and overall functional decline. For therapists, this means nutrition and hydration should remain on the radar—not because we’re primary providers in those areas but because they influence outcomes in almost every domain of rehabilitation.

Integumentary System and Aging

The integumentary system is another area where aging brings significant changes, which many of us have witnessed firsthand with our parents or older relatives. A light bump into a countertop or even a pet jumping on their lap can result in the skin tearing or bleeding. This fragility is a direct result of age-related changes such as reduced collagen and elastin, which make the skin thinner and less resilient. Sensory changes also play a role, as many older adults experience diminished sensation, making it harder to detect minor injuries or pressure before they become larger problems.

When spinal cord injury or other neuropathies are present, these issues are compounded. Impaired sensation below the level of injury, combined with already fragile skin, significantly increases the risk for breakdown, wounds, and pressure injuries. This combination makes skin care, positioning, and pressure management some of the most critical components of long-term care and rehabilitation for older adults with SCI.

Integumentary and Wound Healing

Another key point is that everything heals more slowly in older adults. Despite complicating factors, wounds and injuries take longer to recover simply due to normal aging. When you add in spinal cord injury, that slower healing trajectory becomes even more complex. Skin breakdown, surgical wounds, or pressure injuries can persist for much longer than expected, which increases the risk of infection and other complications.

And that’s before we even factor in chronic health conditions like diabetes, vascular disease, or malnutrition, which further delay recovery. It all returns to the reality that nothing heals as quickly as we’d like in this population. For clinicians, that means expectations, care plans, and patient education must be adjusted with the understanding that healing will be prolonged and requires vigilant management.

Integumentary and Wound Considerations

The most important strategy for older adults is prevention—doing everything possible to reduce the risk of wounds before they occur. Of course, prevention will never be perfect, but if you’re not accustomed to working with this population, it’s easy to underestimate just how fragile the skin can be and how easily complications arise.

I remember one of my first experiences in this area with a patient in a wheelchair. I had removed the leg rests, and when the patient let their leg down, it barely touched the connection point where the footrest attached to the frame. That tiny contact caused a skin tear. The wheelchair wasn’t sharp or unsafe—it was simply that the patient’s skin was so thin and vulnerable that even light contact was enough to cause an injury.

Wheelchairs, slide boards, and body-weight support harnesses all need extra scrutiny. These devices aren’t designed to be dangerous, but exposed metal, edges, or straps can easily catch fragile skin. For patients with SCI, that risk is even higher. Every piece of equipment needs to be double-checked for potential pressure points, rubbing, or pinching.

Edema management is another critical factor since unmanaged edema accelerates skin breakdown. Hydration also plays a role, yet many older adults are reluctant to drink for a variety of reasons, which compounds the risk. Positioning remains foundational. While we often teach the standard “turn every two hours” guideline, some older adults may require even closer monitoring depending on their condition, skin quality, and overall health status.

The bottom line is that skin care in older adults with SCI requires slowing down, being hyper-vigilant, and making prevention part of every interaction.

Musculoskeletal System and Aging

It’s very common for older adults to present with low bone mass—nearly half fall into that category. Osteoporosis becomes particularly significant in women, with more than a quarter over age 65 meeting diagnostic criteria. That’s based on the classic DEXA scan T-score measure. This creates obvious fracture risk considerations, which we’ll get into more in a moment.

Osteoarthritis is another condition that becomes almost universal with age. By the time adults reach 75, nearly 90% are affected. The result is pain, inflammation, disability, and limitations in function due to changes in joint structure. From a therapy perspective, many joint changes in older adults fall within the expected “normal” range for their age. Active range of motion tends to diminish more than passive range, and the degree of change isn’t uniform across all joints. For instance, shoulder flexion and hip extension show significant reductions, while knee range of motion is often well preserved. Having clear guidelines for what’s typical in older adults is vital so that you can differentiate between normal changes and pathology.

Postural adaptations have also become increasingly common. One of the most recognizable patterns is a forward head posture with thoracic kyphosis and cervical hyperextension. This posture is also one of the reasons central cord syndrome is such a risk in older adults—falls combined with a hyperextended cervical spine increase susceptibility. Other postural changes, like hip and knee flexion contractures, reduce efficiency across functional tasks, including transfers, walking, and self-care.

Fracture risk is a significant concern in this population, particularly for women with osteoporosis. That means therapy planning requires some caution. Excessively dynamic or high-resistance interventions can increase fracture risk. Balancing strengthening with safety, tailoring programs to bone health, and using interventions that minimize impact loading are all important considerations for reducing risk while maximizing function.

Cardiopulmonary System and Aging

Cardiopulmonary Changes in Older Adults

Of course, we also expect some of the traditional cardiopulmonary and vascular changes accompanying aging. Lung capacity decreases, which can affect endurance and activity tolerance. The heart and vascular system also undergo structural changes—valves stiffen, arteries and the aorta lose elasticity, and blood pressure tends to rise as the heart has to pump harder against those more rigid vessels.

These changes are considered part of the normal aging process, but they still significantly impact how older adults tolerate activity, recover from illness or injury, and respond to therapy. For individuals with SCI, layering these cardiovascular and pulmonary shifts onto the demands of rehabilitation only adds to the complexity we have to account for in planning and delivering care.

Cardiopulmonary Considerations

One of the first things to keep in mind with older adults is the impact of beta blockers. If you dose exercise intensity by heart rate, this becomes critical. Beta blockers typically blunt heart rate response by about 10 to 15 beats per minute, which makes standard formulas for estimating max heart rate less reliable. Sometimes clinicians adjust by simply subtracting that 10–15 beats, but there are also alternative formulas. The Tanaka equation, for example, tends to be more accurate in older adults than the traditional Karvonen formula (220 minus age). Another option, especially for those on beta blockers, is Brunner’s formula, which some consider best practice. If you’re using heart rate as your dosing method, you need to know whether your patient is on a beta blocker and adjust accordingly.

Warm-ups and cooldowns are another important piece. While they can be difficult to build into a session—especially in time-pressured settings like skilled nursing—older adults benefit enormously from them. Warm-ups and cooldowns help manage osteoarthritic stiffness, support cardiovascular health, and reduce the risk of post-exercise complications. Even a few extra minutes can make a meaningful difference. Adding in breathing or recovery strategies at the end of a session is also a valuable tool.

Of course, when you layer in spinal cord injury, there are additional considerations. Autonomic dysfunction is one of the most significant problems in the cardiopulmonary realm. These patients can present with atypical cardiovascular responses, meaning you can’t always rely on standard expectations of blood pressure or heart rate behavior. That makes individualized monitoring essential, with tailored exercise prescriptions based on the patient’s specific presentation. And then, as we’ll cover further, musculoskeletal changes add yet another layer of complexity in planning safe, effective therapy for older adults with SCI.

Nervous System and Aging

Normal Aging and the Nervous System

Sarcopenia is another critical factor in aging that has major implications for function. It refers to the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, one of the biggest drivers of functional decline. With each passing decade, we see motor unit loss, meaning muscles are less coordinated, more prone to fatigue, and overall weaker. This process can begin as early as age 30 but accelerates significantly after 50, with some research suggesting up to a 10% loss of muscle mass per year in later decades.

The mechanisms behind sarcopenia aren’t fully understood. Hormonal shifts and genetic factors play a role, but lifestyle factors are a major contributor. The encouraging part is that much of this decline may be preventable—or at least slowed—through physical activity. This is one of the strongest arguments for why therapists should be actively engaged in supporting older adults throughout the aging process.

Alongside sarcopenia, there are also important changes in the nervous system. Myelin breakdown leads to slower conduction speeds, and we see fewer and less consistent synaptic inputs. The result is a loss of fast-twitch (type II) muscle fibers, while slow-twitch (type I) fibers are better preserved. This matters because type II fibers are responsible for power, quick reactions, and balance recovery—all critical fall prevention and independence functions. The disproportionate decline of fast-twitch fibers is part of the reason older adults are more vulnerable to falls and functional loss, and it highlights the importance of targeted interventions to preserve strength, coordination, and speed as much as possible.

Neuromuscular Changes

Older adults often see a shift in muscle fiber composition, with a higher proportion of type I (slow-twitch) fibers as type II (fast-twitch) fibers are lost. This matters because type II fibers are closely tied to power—force multiplied by velocity. Power allows someone to generate quick, forceful movements, and its decline is a critical predictor of overall function.

When muscle power diminishes, we see downstream effects on essential daily activities. The ability to respond to a loss of balance, recover from a trip, or perform dynamic movements like rising from a chair depends heavily on power. Much like gait speed has emerged as a key marker of health and functional independence, power is now recognized as another vital indicator for therapists to assess.

That means we need to ask ourselves: What is my patient’s ability to generate power? And if it’s impaired, should I incorporate more speed-focused or power-focused interventions into their program? Training for strength alone isn’t enough; incorporating velocity into movement patterns may be just as important, if not more so, for helping older adults maintain independence and prevent falls.

Fall Risk in Older Adults

Co-morbidities

One of the most significant complicating factors in addressing falls is that it never deals with just one issue in older adults. Instead, it’s an interconnected web of challenges that span every body system. People often say geriatrics is a generalist field, but it requires at least a working expertise across nearly all systems—cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, neurological, integumentary, gastrointestinal, urologic, and more. Each system brings its chronic conditions, comorbidities, medications, and best practices to consider.

When you layer spinal cord injury on top of that already complex picture, the level of challenge increases dramatically. SCI adds mobility impairments, autonomic dysfunction, altered sensation, and equipment needs into a multifaceted case. The result is that fall risk becomes not just a concern but a central theme of care planning.

This is why prevention is so critical. With SCI in older adults, our time and focus must be heavily directed toward minimizing falls wherever possible. It’s about avoiding injury and protecting independence, quality of life, and long-term outcomes. Prevention strategies—whether through strength and power training, environmental modifications, caregiver education, or equipment selection—are among the most essential tools we can bring to this population.

Falls and Aging

Falls are extraordinarily common in older adults—about one-third of individuals over 65 experience a fall each year. Beyond the sheer prevalence, the consequences are profound. Falls are a leading cause of injury-related hospitalization in this population, and they carry a high burden of both morbidity and mortality.

The financial costs are also staggering, with billions spent annually on fall-related care, rehabilitation, and long-term support. But the personal costs are even greater. A single fall can set off a cascade of complications: fractures, loss of independence, fear of falling again, reduced activity levels, and ultimately a decline in overall health. When SCI is added to the picture, these consequences are amplified. That’s why fall prevention isn’t just one piece of the puzzle—it’s one of the most critical priorities in caring for older adults.

Fall Prevention

Fall prevention is one of our most difficult challenges, and it’s natural to ask, “What’s the silver bullet?” The reality, of course, is that there isn’t one. Falls are far too diverse, and each individual brings their own unique set of risk factors. That’s why best practice is not a single intervention but a combination of strategies that address the multifactorial nature of falls.

Take a simple example: someone slips on water. On the surface, it looks like an environmental accident, but when you dig deeper, you might find they got up quickly because of incontinence, they couldn’t recover balance because of lower extremity weakness, their posture limited their reaction time, and their vision changes prevented them from detecting the hazard. Rarely is it one factor in isolation—the interplay of many.

This is why root cause analysis is so valuable. Identifying and prioritizing the most relevant contributors allows us to tailor interventions that matter for that individual. Prevention is always more impactful than treatment, and it requires individualized approaches. Tools and assessments help stratify risk, but no single measure captures the whole picture. Ultimately, fall prevention is one of therapists' most important roles in caring for older adults.

Every fall is a roll of the dice. Normal aging often follows a slow, steady path with predictable changes, but one fall can completely alter that trajectory—changing lifespan, function, and quality of life instantly. That’s why every fall prevented has an enormous impact, even if it goes unrecognized. The irony is that when you do your job well, you rarely know it. You can note that a patient hasn’t fallen, but you can’t quantify how many falls you’ve prevented. Still, the unseen prevention is often the most powerful work we do.

Assistive Device Use With Aging

It’s also important to consider when and how to introduce assistive devices. While walkers, canes, and other supports can certainly reduce fall risk in the short term, they’re not without their downsides. Using a more restrictive device often makes covering distance more taxing, which can limit activity and independence. The key is introducing the correct device at the right time—early enough to provide needed safety, but not so soon that it unnecessarily restricts the individual.

Waiting too long can also create problems. If cognitive impairment progresses before a device is introduced, the person may not be able to learn how to use it safely or consistently. That makes timing especially tricky. There isn’t a universal rule or “perfect” point for introducing a device—it often comes down to clinical judgment, experience in long-term care, and attention to the individual’s unique needs.

Shared decision-making plays a significant role here, too. If needed, talking openly with the patient (and their caregivers) about the pros and cons helps balance safety with independence and ensures the plan reflects the individual’s goals and preferences.

Co-Morbidities with Higher Fall Risks

There are also a variety of conditions that place older adults at greater risk for falls. We don’t need to go into the details of every single one, but keeping a clear picture of which comorbidities heighten that risk is essential. This awareness helps you prioritize who to screen more thoroughly, where to focus fall prevention efforts, and which individuals may require earlier or more intensive interventions.

We’ve alluded to this throughout—conditions like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, arthritis, vision impairments, neurological disorders, and cognitive decline all compound the risk. Having that vision of the “high-risk” profiles allows you to be more proactive, targeting your prevention strategies to the most vulnerable and ensuring timely and meaningful interventions.

Variations in Patient Centered Goals

Shared decision-making is really at the heart of being effective with older adults. Often, the goals of the therapist, the family, and the patient don’t fully align. However, if the patient is the decision-maker, their priorities should be the primary driver of the plan of care. Our role is to guide, educate, and support—but ultimately, it isn’t our or the family’s decision. The best outcomes usually come when we find a middle ground where safety, function, and patient values intersect.

One structured approach that can be very helpful here is the What Matters Most tool. It provides a framework for clarifying a patient’s priorities and opens up meaningful conversations between the patient, family, and care team. These discussions shape therapy goals and help ensure that care reflects what is most important to the individual.

It’s equally important to ensure advanced care planning conversations are happening if they haven’t already. Documenting decisions about future care ensures that if the patient becomes incapacitated, their wishes are clearly understood and respected.

Another point worth emphasizing is that not every older adult strives for improvement in the traditional sense. Some may prioritize comfort and quality of life over functional gains. This is where palliative care becomes highly relevant. Unlike hospice, which is end-of-life focused, palliative care supports individuals who may not be dying but want to focus on symptom relief, pain management, and reducing stress rather than pursuing aggressive rehabilitation. Therapists are vital here, helping patients maintain dignity, comfort, and participation in meaningful activities, even when improvement isn’t the goal.

Individuals with Late Onset Spinal Cord Injury

Kristen: I’ve been fortunate throughout my career—and partly because Kevin and I have been married for quite a while—to gather insights from my practice and the conversations we’ve had at home. Living in Florida, the retirement capital of the U.S., I was exposed very early on to a large number of older adults with spinal cord injuries. That shaped my perspective quickly.

I would often come home reflecting on how different it was to manage SCI in older adults compared to younger individuals. The needs, recovery trajectories, and complications required me to adapt my approach. Those early experiences highlighted stark differences and made it clear that working with this population was not just about applying the same principles across the board but about tailoring care to the realities of aging.

So with that context, I want to highlight some common complications briefly. Kevin has already walked us through many changes that occur with normal and abnormal aging. Still, when SCI enters the picture, those changes interact, creating particular challenges.

Common Medical Complications Following SCI

With spinal cord injury, there are several well-documented secondary complications that we’ve known about for decades. These complications occur across the lifespan, but they’re particularly significant in older adults because of the way they interact with age-related changes. As clinicians, prevention has to remain a primary focus. Whether it’s through our interventions or empowering individuals living with SCI to manage risks themselves, the goal is to keep these complications from developing in the first place. Once they do, quality of life and social participation are often severely impacted.

That’s why understanding who is most at risk is so important. It allows us to screen appropriately, anticipate problems, and target interventions. For example, respiratory complications are more common in individuals with higher-level injuries, and older adults are even more vulnerable due to decreased physiologic reserve. Pressure injuries remain one of the most prevalent and costly complications, and we’ll be looking at those in more detail. UTIs are another frequent concern, as are other secondary health issues that come with impaired mobility and function.

What’s striking is that despite years of study, none of these problems have been “solved.” In my nearly 15 years of practice—and for those who have been in the field even longer—it’s clear we’re still having the same conversations about pressure injuries, UTIs, and other complications after SCI. That tells us these are not simple, one-dimensional problems. They’re multifactorial, influenced by medical, environmental, and social factors. While progress has been made, these complications remain central challenges in SCI care, demanding clinicians' vigilance, creativity, and ongoing problem-solving.

Older Adults with SCI

When we look at older adults with SCI, the literature highlights some clear differences in acute treatment and rehabilitation compared to younger populations. Ahn et al. (2015) examined individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury who were aged 70 and older. Many of these patients presented with less severe, incomplete neurologic injuries, which is consistent with the central cord and incomplete tetraplegia patterns we’ve already discussed. Even so, they experienced delays in transfers to specialized treatment centers, slower admission to surgery, higher rates of adverse events, and greater mortality.

I’ll share an example that brings this to life. A colleague in acute care once called me about a patient in their late 60s who had fallen. All the imaging came back clean—brain, spinal cord, everything cleared. The medical team was ready to discharge, but he sat the patient up during his evaluation and immediately noticed significant trunk instability and weakness in the hands. The legs were relatively strong, which made it easy to overlook, but he recognized the red flags. This wasn’t someone safe to go straight home. It didn’t fit the “classic” spinal cord injury picture we often associate with younger patients, but it was SCI nonetheless. That case underscores how important it is to recognize the varied and sometimes subtle presentations of spinal cord injury in older adults.

Wilson et al. also found that elderly SCI patients had higher hospital readmission rates at both one and five years post-injury. Those readmissions drove significantly higher direct healthcare costs across acute care, inpatient rehab, and home health services. For us as rehabilitation professionals—whether PT, OT, or another discipline—that reality highlights our critical role in reducing complications and preventing rehospitalization whenever possible.

Pressure injuries are a prime example. Kevin mentioned that they’re multifactorial, but older adults are at even higher risk. That’s why skin management plans must be aggressive and proactive. While physicians and nurses are certainly part of this, therapists often take the lead in identifying risks, implementing prevention strategies, and educating patients and families.

Respiratory dysfunction is another major complication seen more frequently in older adults at the time of SCI. Those with more severe neurologic injuries face elevated risks for pneumonia, atelectasis, and other pulmonary issues. This makes early respiratory management, monitoring, and therapy interventions absolutely essential to improving outcomes and preventing secondary decline.

SCI and Aging Related Clinical Practice Guidelines

With that in mind, it’s essential to highlight the role of aging-related clinical practice guidelines. As Kevin mentioned earlier, guidelines are invaluable when working with older adults. Clinical practice guidelines are often the best place to start if you’re ever uncertain about a particular aspect of care for this population. They represent one of the highest levels of evidence, drawing from systematic reviews and consensus across a vast body of research.

What makes them especially useful is that they tend to be comprehensive and reflect roughly the past decade of literature, which means they capture current trends and best practices. While we always have to be mindful of the fact that older adults with cognitive impairments or multiple comorbidities are often underrepresented in the research, guidelines still provide a solid framework. They help us anchor our clinical reasoning, ensure we’re aligned with evidence-based practice, and give us a foundation from which we can adapt care to the complexities of each case.

Clinical Practice Guidelines and Aging

Anytime a clinical practice guideline is available, it’s an excellent place to start because it provides a clear foundation of recommendations supported by a robust body of evidence. That said, Seijas et al. (2024)published an extensive review just last year examining the scope of existing CPGs for spinal cord injury, and they found a significant gap regarding guidelines specific to aging with SCI.

If you’re familiar with the Spinal Cord Injury Consortium or the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA), you know they’ve developed an impressive library of guidelines covering nearly every SCI-related topic imaginable—from outcomes to bladder and bowel management, skin care, respiratory considerations, and more. These are updated roughly every 10 years and remain highly respected resources. But even within these, aging is often mentioned only in passing. Many guidelines acknowledge the need for age-related considerations, yet they stop short of providing detailed recommendations tailored to older adults with SCI.

Part of the challenge is that older adults—particularly those over 65—are often excluded from the randomized controlled trials that form the backbone of these guidelines. There’s also inconsistency around definitions: Is an older adult someone over 50? Over 65? And how do outcomes differ between frail older adults and otherwise healthy older adults who sustain an SCI later in life? These questions remain unresolved, limiting the guidelines' ability to give us concrete direction.

The review clearly highlights this gap. They noted that while the literature on aging and SCI has expanded, there is still a lack of high-quality, detailed recommendations for rehabilitation professionals. Much of what exists focuses on medical or surgical management—interventions, medications, acute care considerations—rather than on rehabilitation and long-term function.

That said, there were some takeaways for therapists. The review emphasized strong recommendations for:

Systematic fall risk assessments

Regular pressure injury risk screening

Sitting surface and pressure evaluations at least every two years (or more frequently)

Nutritional status monitoring and intervention as needed

Incorporation of aerobic exercise as part of rehabilitation

However, even these stop short of giving specific, detailed protocols. For example, aerobic exercise is strongly encouraged, but no defined frequency, intensity, or duration parameters are explicitly tailored to older adults with SCI.

So from a rehabilitation standpoint, we’re still left pulling information from multiple sources—general aging literature, general SCI guidelines, and our clinical expertise—and applying it to the unique individual in front of us. The lack of targeted CPGs underscores how important it is for clinicians to remain flexible, evidence-informed, and patient-centered when working with this complex population.

Rehabilitation Strategies for Older Adults with SCI

When we think about rehabilitation strategies for older adults with SCI, several key areas to focus on are walking interventions, functional mobility such as bed mobility and transfers, structured exercise programming, and wheelchair considerations—each of which can be complex and highly individualized.

But before diving into those interventions, it’s worth pausing again to emphasize the importance of shared decision-making. This model is central to how we approach care. It recognizes that patients are not passive recipients but active participants in their rehabilitation. While most of us would say we include our patients in decisions, it’s easy—especially as we gain confidence and experience—to slip into the role of telling people what they should do, based on our expertise, instead of truly exploring their goals, values, and preferences.

Shared decision-making is a structured process that asks us to step back and frame our role differently. Our job is to present the available options, explain the risks and benefits, and then help the individual weigh those choices against their lifestyle, priorities, and preferences. This often requires us to put aside our values and recommendations, which can be very difficult—especially when it involves someone close to us.

For example, in our own family, my father-in-law is aging with a spinal cord injury. At a certain point, it was clear from a clinical standpoint that it was time for him to transition to a power wheelchair. I laid out all the logical reasons why this would increase safety and independence, but he had no interest in doing so. Despite the challenges, he preferred to continue with his current level of mobility. As a physical therapist and a family member, I found it hard to accept. But ultimately, it was his choice, and the shared decision-making model helped me step back and recognize that my role was to educate, not dictate.

This illustrates why the process is so important. In the fast-paced healthcare environment, it’s easy to rush from one task to the next, focusing on efficiency and outcomes. Shared decision-making requires us to slow down, sit with the patient, and truly explore what matters most to them. The steps are straightforward—invite the patient to participate, help them investigate and compare options, and support them in making decisions that align with their goals—but the discipline to implement them consistently makes the difference.

Keeping this mindset front and center allows all our interventions—whether walking, transfers, exercise, or wheelchair recommendations—to be meaningful and patient-driven rather than therapist-driven.

Rehabilitation Strategies for Older Adults with SCI

That approach frames the essence of patient-centered care. Over time, I’ve shifted in how I explain interventions, moving away from presenting them as directives and instead framing them as choices. I lay out the different options, describe what each intervention entails, and then talk through the likely outcomes: “If we choose this path, here’s what you can probably expect. If we go this route instead, these are the potential outcomes.”

This way, the focus isn’t on what I think is best but on giving the patient the knowledge to make an informed decision about what feels right for them. Whether we’re talking about walking interventions, exercise programs, transfers, or wheelchair selection, it comes back to the same principle: aligning the care plan with the individual’s goals, values, and preferences. That shift not only empowers patients but also makes the rehabilitation process more collaborative and sustainable.

Shared Decision Making: The SHARE Approach

These are decisions that belong to the individual. Our role is to assess and understand a person’s preferences and values—not to assume them. And I’ll admit, many times throughout my career I’ve fallen into that trap of thinking, “I know what this person wants.” Projecting our judgment is easy, especially when we feel confident in our clinical reasoning. But that shortcut often bypasses the patient’s voice.

What truly matters is taking that extra moment to sit down and ask directly, “What do you want from this intervention, from this mobility plan, from this stage of your recovery?” That intentional conversation ensures that their goals authentically guide the plan of care.

From there, the next step is to evaluate the patient’s decision. This doesn’t mean overruling them if their choice doesn’t perfectly align with medical recommendations. It does mean making sure they understand the ramifications and weighing the risks and benefits together so the decision is as informed and comprehensive as possible. That process honors their autonomy while ensuring they’re fully aware of the potential outcomes of their choices.

Social Determinants of Health

Kevin already touched on the social determinants of health. While I won’t go into all of them here, four in particular consistently shape the way I deliver interventions and frame discussions with clients: caregiver assistance, home environment, access to rehabilitation, and socioeconomic status.

These themes run underneath almost every clinical decision we make. Whether someone has a caregiver who can reliably assist influences everything from the complexity of interventions we prescribe to the equipment we recommend. The home environment determines whether those recommendations are feasible—what works in a single-level home may not translate to a two-story condo. Access to rehabilitation also varies widely, shaping both the intensity and continuity of care. Socioeconomic status often dictates what’s realistic regarding equipment, home modifications, and even adherence to long-term health strategies.

This is where a statistical understanding of broader trends in the U.S. older adult population becomes useful. Knowing the common challenges—fixed incomes, housing patterns, or caregiver shortages—helps us contextualize our work. The more we understand the background, the more effectively we can narrow in on what’s most relevant for each client.

Outcomes for Older Adults with SCI

Functional benchmarks focus on what the person can do daily, like safe transfers, propelling a wheelchair, or completing grooming and feeding with adaptive strategies.

Progress takes longer because of factors like skin fragility, sarcopenia, slower healing, and reduced cardiovascular reserve, so goals need to be broken into smaller steps and set over longer timeframes.

Quality of life and participation are central, since older adults prioritize comfort, meaningful activity, and reduced caregiver burden over traditional medical gains.

The clinician's role is to balance aspiration with realism, maintain open communication, and recognize that stabilization or prevention of decline can be just as valuable as visible improvement.

Functional Mobility Considerations for the Older Adult with SCI

First, some functional mobility considerations should be considered when considering older adults with SCI.

Bed Mobility

Bed mobility after SCI in older adults often looks very different from what is taught as “classic” techniques, because pre-existing musculoskeletal changes, arthritic limitations, or surgical histories frequently alter what is safe or feasible. Traditional approaches like log rolling, supine-to-long-sit transitions, or the C-maneuver are often a starting point, but modifications are almost always required.

Joint range of motion and pain status are central to determining whether a technique is appropriate. Many older adults with SCI present with arthritic changes, rotator cuff repairs, or joint replacements that make repetitive weight-bearing through the shoulders, elbows, or wrists painful or unsafe. Hamstring tightness, limited hip external rotation, or knee stiffness can also restrict positions like the ring or long sit, which are integral to bed mobility strategies. Even if a joint technically moves through the range, repeated practice can lead to further breakdown rather than progress if it provokes pain.

Because of this, assessment must go beyond muscle strength and paralysis pattern to include orthopedic history, surgical precautions, and tolerance to loading of the upper extremities. For example, a hip replacement combined with paralysis may mean ring sit strategies are contraindicated due to joint instability. Similarly, prior humeral fractures or rotator cuff repairs may rule out reliance on pushing through the arms.