Editor's note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Overcoming Compassion Fatigue in Our Work Environment, presented by Neely Sullivan, MPT, CLT-LANA, CDP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List three physiological effects of chronic uncertainty and stress.

- Recognize the causes, symptoms, and consequences of stress and compassion fatigue.

- Describe assessment tools used to understand levels of compassion fatigue in your work environment.

- Identify effective strategies to prevent/minimize stress and to improve health and work satisfaction.

Overview

Let's start with why I put this presentation together for you. l, like you, have been living and trying to figure out how to best serve my clients during a pandemic. Also, as the cases tend to wax and wane while we live in this pandemic, I have noticed that my clients need me more than ever. Over the last two years, I've had to dust off a lot of old skill sets. Sometimes in a matter of days, weeks, or even hours, I've had to figure out how to approach different complications due to the pandemic, social pressures, or whatever is happening right now. I've had to figure out how to work with my clients to minimize their functional limitations and get them back to their prior level of function.

Dusting off these skill sets and working with new clients with new deficits is in addition to all the other clients I've already been working with. Just like you, I have been scared, tired, and humbled throughout this pandemic, but for the most part, I think we all just want to be there for our clients during this challenging time. As the years have rolled on, our work environments have remained quite intense, and many of my colleagues have started to burn out and lose hope. I put this course together to help us sort through how we approach ourselves, coworkers, and colleagues when we are living with chronic uncertainty and there's no end in sight.

This is relevant because we are living and working in a pandemic, but hopefully, this pandemic will end at some point. Even when it does, we still face many challenges as the healthcare world is constantly evolving. Today I want to give you tools to cope with chronic uncertainty and stress because, unfortunately, that is something we'll probably continue to deal with in the future. Some of the information I present today will be things you may already know, but I want everyone on the same page moving forward.

What is Compassion?

Compassion is suffering with another, participating in suffering, fellow-feeling, and sympathy. Another definition is the feeling that arises when you're confronted with another's suffering and feel motivated to relieve that suffering. There's a biological basis of compassion that has an evolutionary purpose. When we feel compassion, our heart rate tends to slow down, and we start to secrete a bonding hormone called oxytocin. When we look at maps of the brain, the regions of the brain linked to empathy, as well as feelings of pleasure, tend to light up when we feel compassion. This often results in us wanting to approach and care for other people.

Compassion vs. Empathy/Altruism

There is a difference between compassion and empathy, and those definitions are often confused. Empathy is the visceral or emotional experience of another person's feelings. In a sense, it is an automatic mirroring of another's emotion. For example, when you hear a friend is sad because they've lost a loved one, you tear up for that friend. That is empathy. Altruism is an action that benefits someone else. It may or may not be accompanied by empathy or compassion. Although these terms are related to compassion, they're not identical. Compassion often involves an empathetic response and altruistic behavior, but compassion is the emotional response when we perceive suffering and involves a real, authentic desire to help.

Since we often think empathy and compassion are the same, we often experience compassion fatigue, which might be more accurately called empathy fatigue, because true compassion has another level of depth and skill than empathy. Compassion is the emotions I feel for you, and I understand you and want to help. Any kind of professional caregiving practice, including nursing, therapy, or social work, thrives within the context of caring, empathetic relationships between the clinician and the client. This relationship is the reason I became a therapist. However, this necessary empathetic relationship can also contribute to compassion fatigue if we don't take steps to lessen this condition.

We know that our work as therapists is technically demanding. We have a lot of expectations placed on us all the time, including technical accuracy expectations, competing time schedules, and logistics that we're always working through. It also demands a lot of our humanity, minds, hearts, and spirits. All of these things are unavoidably challenged by the fact that we face suffering daily, including our clients hurting or perhaps dying. Suppose we're unaware, not trained, and not skillful about attending to ourselves as we are to all the other technical duties and our clients. In that case, we risk an inability to provide good service to our clients and the breakdown of our well-being and potentially in other areas of our life.

The Physiological Evidence of Prolonged Stress

There are a lot of people who have thought about and researched what we're talking about today. Dr. Rachel Remen, MD, was the first woman to be chosen to be on the Faculty of Stanford Medical School. She said, "The expectation that we can be immersed in suffering and loss daily and not be touched by it is as unrealistic as expecting to be able to walk through water without getting wet." I think this quote eloquently illustrates the inevitability of compassion fatigue, especially for those in the helping profession.

Understanding and preparing for work with our clients who are living through this pandemic and experiencing trauma also requires us to be mindful of the stressors that require our attention. We also must develop strategies that support our resilience. Today I will focus on the implications of helping ourselves and our colleagues. Specifically, I'm going to focus on compassion fatigue. Awareness regarding the inevitability of all of our occupational stresses, like compassionate fatigue, is an essential first step in building resilience among therapists.

Case Study

Let's begin with a case study. I want you to meet Terrell and as you read his story, note if you can identify with any part of it.

Terrell attended therapy school and planned a career in long-term care communities. During Terrell's childhood years, his mother had multiple admissions into long-term care communities for fractures and falls. The nursing/therapy staff and the family became very familiar with each other during these repeated admissions. This motivated Terrell to pursue a career as a therapist. After graduation, Terrell began working in a skilled nursing community. He didn't take a lot of breaks and quickly acquired the skills needed to work in this environment. He soon became a leader.

Within a short time span, three of his clients died. The patient census remained high, and the workload remained intense. Terrell began viewing his work as drudgery. He couldn't even arrive at work on time, and when he did arrive, he rarely offered to be a consistent caregiver for any challenging clients. His coworkers observed his changing behavior as he struggled to find some work-life balance. His manager also noticed the behavior changes and attempted to adjust Terrell's schedule to work longer shifts, meaning that he would work longer but would have more time off.

This adjustment started to take a toll on Terrell physically and emotionally, and after a period of time, he decided he had to change things up. He started working in the outpatient clinic in the skilled nursing community, but this new work environment didn't diminish his involvement with certain clients and their families. Although Terrell attempted to adjust to this new setting, he continued to care for clients with end-of-life respiratory disease processes. Eventually, he left this position to pursue a less stressful work environment.

This is an example of compassion fatigue. Can you identify with Terrell's story?

Stress

One of the components of compassion fatigue is stress. Stress is your body's response to changes that create taxing demands. There are a lot of different sources of stress. Stressors are not always limited to situations where some external situations create a problem.

Internal Sources of Distress

There are also internal events like feelings and thoughts, and habitual behaviors that can cause negative stress. A common internal source of stress includes fears, such as being afraid of public speaking or chatting with clients. It also includes repetitive thought patterns or worrying about future events, such as waiting for some type of medical test or if you know that your job will be restructured and you're waiting to hear how it will be restructured. There are also unrealistic perfectionist expectations, which I think many of us probably are guilty of in the therapy world. Other sources of internal stress include overscheduling ourselves. In addition, procrastination, failing to plan, and speaking up for yourself and your needs are internal sources of distress.

Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity (CTRA)

On the biological side, let's talk about the concept of the conserved transcriptional response to adversity (CTRA). This is where your hypothalamus responds to some type of threat that activates your central nervous system, which is in charge of your fight or flight response. In your brain, the hypothalamus tells your adrenal glands to release adrenaline and cortisol stress hormones. When it releases these hormones, they rev up your heartbeat and send blood rushing into the areas that need it most in an emergency, whether that's your muscles, heart, or other important organs. When that perceived fear is gone, ideally, the hypothalamus should tell all the systems to return to normal. But if the central nervous system fails to return to normal, or if the stressor doesn't go away, that response will continue.

Exposure to these prolonged threats activates a conserved transcriptional response to adversity that involves upregulation of your pro-inflammatory immune response, which is in charge of combating pathogens and infections. It also downregulates your immune response, targeting pathogens and viruses. The short-term benefits are increased survival skills and improved physical recovery. Still, if the threat doesn't go away, as we've seen during this pandemic, the long-term effects are increased inflammation, increased vulnerability to viruses, and increased risk of death.

The Body's Reaction to Stress

We talked a bit about what the central nervous system and the hypothalamus do regarding stress, but what about other systems? Those stress hormones affect your respiratory and cardiovascular systems as well. During the stress response, you may notice yourself breathing faster to distribute oxygenated blood to your body quickly. Stress can make breathing difficult or harder if you already have a breathing problem, such as asthma or emphysema. If you're under stress, your heart also pumps faster, so stress hormones cause your blood vessels to constrict and divert more oxygen to your muscles, so you'll have more strength to take action, raising your blood pressure.

When your digestive system is under stress, your liver produces extra glucose, which gives you a boost of energy during a stressful situation. If you're under chronic stress and your body can't keep up with this extra glucose surge and chronic stress, it may increase your risk of developing type 2 diabetes. In addition, the rush of hormones, rapid breathing, and increased heart rate can also upset your digestive system. Increased stomach acid makes you more likely to have heartburn or acid reflux. We often hear that stress is related to ulcers but doesn't necessarily cause ulcers. If you have existing ulcers, you are at an increased risk of them acting up. Stress can also affect how food moves through your body, leading to diarrhea, constipation, nausea, or stomachaches.

When stressed, your muscular system is often on high alert, or your muscles start to tense up to protect themselves from injury. They tend to release again once you relax, but your muscles may not get the chance to relax if you're constantly under stress. Those tight muscles may cause chronic pain, chronic headaches, or back and shoulder pain. Over time this can set off an unhealthy cycle if you stop exercising or turn to pain meds for relief.

In addition, if the stress continues for a long time, it can lead to dysfunction in your reproductive system. Men's testosterone levels can begin to drop, interfering with sperm production and causing impotence or erectile dysfunction. Chronic stress can also increase the risk of infection in male reproductive organs, like the prostate. For women, stress can affect the menstrual cycle and can magnify the physical symptoms of menopause.

This weakens the immune system, which can be a plus for immediate situations. This stimulation can help you avoid infections and heal wounds. Still, over time, the stress hormones start to weaken that immune system and reduce your ability to respond to foreign invaders. People under chronic stress are more susceptible to viral illnesses like the flu and the cold and other infections like COVID. Stress can also start to increase the time it takes for you to recover from illness or injury.

Chronic Uncertainty

From the stress of the pandemic and social and political unrest, perhaps you've had a level of job uncertainty, or maybe you've had illnesses within your family or various levels of isolation. All of these contribute to a sense of uncertainty, but what is chronic uncertainty? It is when we feel uncertainty for an extended amount of time, but how might this long-term uncertainty experienced by an entire population start to affect community health? Uncertainty means haziness or doubt. We have to expend a lot of effort trying to predict what will happen and preparing to deal with all the different outcomes.

The stress of chronic uncertainty is among the most harmful stressors we experience. But when living with prolonged uncertainty, it can help to recognize that constant ambiguity amplifies the brain mechanism essential for our survival. Chronic uncertainty is the brain trying to determine the best course of action for survival. Chronic uncertainty is closely related to stress and anxiety. When you combine uncertainty with threat, you get anxiety and stress.

Chronic Uncertainty and the Brain

During times of uncertainty, neurons in the ventral hippocampus are activated as part of the brain involved in memory and emotions. These neurons, in turn, activate the hypothalamus, which, as previously discussed, is the brain region that triggers avoidance behaviors. Uncertainty emerges when the way forward is not clear. Anxiety and stress emerge when the perceived way forward may contain a threat. There's a balance between avoiding potentially dangerous things and exploring them because there might be a reward. We are continuously evaluating both things. What we do, how we react, and what action we choose depends on how much we weigh these things.

Sending certain pieces of information between different brain parts often involves synchronization between the brain signals in these regions. The prefrontal cortex plays an essential role in this process and determines which information to focus on and which to ignore. It makes decisions based on signals from other parts of the brain, like the hippocampus, where the anxiety neurons reside. Without synchronization, the brain would have more difficulty deciding what's important and what to focus on.

With certain anxiety disorders, we see problems with appropriately filtering information. We know that anxiety is necessary because if we didn't experience anxiety, we would do overly dangerous things. However, pathological situations arise when for whatever reason, the brain doesn't seem to be able to tune anxiety properly. It sends messages to your brain and the rest of your body to avoid. I think we see this creeping up a lot in the current environment that we live in. In most cases, the human brain is good at managing anxiety. We can think about multiple scenarios and outcomes and prepare ourselves for them before they happen.

The problem is that constantly imagining, predicting, and preparing for bad outcomes take a toll on us psychologically and biologically. This may cause exaggerated reactions to perceived threats. In these reactions, our cognitive strength can be turned against us. Our bodies react to hypothetical threats as if they're right in front of us. We might experience chronic stress symptoms if we break out into sweats or have heart palpitations or a rapid heartbeat. Because so many people worldwide are living in a state of anxiety, at least partly due to the effects of the pandemic, we might start to see people showing more of these kinds of responses to potential threats.

When a state of uncertainty drags on for months, those protective cognitive mechanisms start to do more harm than good. In the short term, they're preparing us for positive action to protect us against the potential for injury as it came with stressors in our past. But in the long-term, prolonged activation of the biological stress response can have adverse effects on the brain and the rest of the body, which, as we've already said, may increase the risk for mental health issues and chronic physical diseases.

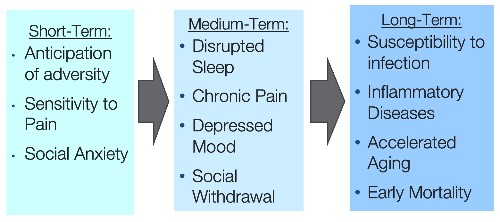

Figure 1. Cognitive, emotional, and health effects of adversity/stress.

Figure 1 ties together everything that I just said. Experiences of adversity or perceived threats start to become biologically embedded and sustain the perceptions of threats for months or years after the original stress has passed. The consequences begin with increased hypervigilance, chronic anticipation of stress or adversity, sensitivity to pain, or symptoms of social anxiety. Think about whether you have experienced these sensations during the past few years. After years of these stressors, you may be at an increased risk for inflammation-related disorders, infection, accelerated aging, and early mortality.

Remember, chronic stress seeps in and affects all of our body systems. As a result, as caregivers, we're all at an increased risk of various health problems, including cardiovascular problems, lower immunity, slower wound healing, poor immune responses to vaccines, and higher levels of chronic conditions like diabetes, arthritis, ulcers, and anemia. We may see our doctors more and use more medications than we did previously. We've also seen poor self-rated health and decreased engagement in preventative health behaviors. There's a lot of research out there that has shown that people are not exercising as much as they were.

Compassion Fatigue

What does this have to do with compassion fatigue, and what do we mean by compassion fatigue? There are a lot of definitions of compassion fatigue, and now it seems like everyone's talking about it. A nurse was the first to describe the concept in her work with emergency room personnel. She identified compassion fatigue as a unique form of burnout that affects individuals in caregiving roles. Figley (2002) and Anewalt (2009) define it as a condition characterized by emotional and physical exhaustion leading to a diminished ability to empathize or feel compassion for others, often described as the negative cost of caring. Caregivers may be traumatized through their efforts to empathize and show compassion. Many of you have felt this way throughout the last few years. This often leads to inadequate self-care behaviors and increased self-sacrifice in that helping role.

Compassion fatigue has been described as secondary traumatic stress resulting from caring for clients and physical or emotional pain or stress. Secondary traumatic stress differs from compassion fatigue, and we'll go through that. Compassion fatigue, especially in the healthcare industry, results from working directly with individuals affected by disasters, trauma, or illness, especially in the healthcare industry. Individuals working in other helping professions are also at risk of experiencing compassion fatigue. Nonprofessionals like family members and informal caregivers of people with chronic illnesses are also experiencing compassion fatigue in record numbers.

Compassion fatigue is characterized by profound physical and emotional exhaustion. It often involves a change in the helper's ability to feel empathy for their clients, loved ones, and coworkers. It is marked by increased cynicism at work and a loss of enjoyment in your career. Eventually, it can become depression, secondary traumatic stress, and stress-related illnesses. The most insidious aspect of compassion fatigue is that it attacks the core of what brought us into this work: our empathy and compassion for others.

Charles Figley has been very instrumental in studying compassion fatigue. He said, "We have not been directly exposed to the trauma scene, but we hear the story told with such intensity, or we hear similar stories so often, or we have the gift and curse of extreme empathy, and we suffer. We feel the feelings of our clients. We experience their fears. We dream their dreams. Eventually, we lose a certain spark of optimism, humor, and hope. We tire. We aren't sick, but we aren't ourselves."

According to Figley's model, the caregiver must have concern in an empathetic ability to feel motivated and to respond when they perceive that the care recipient is suffering. When caregivers have this empathetic response, coupled with an unwillingness to detach from the caregiving situation and the absence of feelings of satisfaction, that is when compassion fatigue occurs. Compassion fatigue may occur because of the caregiver's prolonged exposure to suffering, coupled with any trauma or experience they are going through in their personal life with their life demands.

Compassion Satisfaction

The opposite of compassion fatigue is compassion satisfaction, and this is what we're all shooting for. Compassion satisfaction emphasizes all the positive aspects of helping. It involves the pleasure and satisfaction derived from working in helping caregiving systems. Compassionate satisfaction can be related to providing care to our clients or the satisfaction we get when we work in an excellent care system or with great colleagues. It can also be related to beliefs about ourselves, our ability to make positive changes in the lives of our clients, and how we experience and demonstrate concern for other human beings in our lives. There are a lot of terminologies encompassed in the idea of compassion fatigue, and some of this is overlapping. To sum up some of these concepts, the occupational stress of helping professionals like yourself, serving clients who have been traumatized, is a significant issue for our working environments.

Terminology

Some of the terms to describe this phenomenon are compassion fatigue, which we've now said quite a few times, and what we're talking about today, as well as secondary traumatic stress, vicarious traumatization, and burnout. Although overlap exists between these concepts and terms online, there are distinct differences. Knowing the condition you or your colleagues are experiencing will lead to appropriate interventions for them.

We've already defined compassion fatigue. Vicarious traumatization involves profound changes to your cognitive and core beliefs about yourself, others, and the world resulting from exposure to some type of graphic or traumatic material relating to your client's experiences. For example, during COVID, we may have seen many of our clients or families talk about the incident in detail, or we've had to give really bad news to families during this time. Those things can create vicarious traumatization.

Secondary traumatic stress (STS) presents as a cluster of symptoms nearly identical to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Hyper-vigilance, agitation, mistrust, insomnia, emotional detachment, or participating in self-destructive behaviors are just some of those symptoms. Secondary traumatic stress results from the stress of working with or intimately knowing someone who has been traumatized or is suffering. Perhaps you work with people who have had spinal cord injuries, and you experience secondary traumatic stress because you work so closely and intimately with these clients.

Burnout is a condition that includes a prolonged response to chronic, emotional, and interpersonal stressors on the job. It is typically identified within the three dimensions of exhaustion, cynicism, and a sense of inefficacy. We're seeing a lot of signs of burnout in our therapists right now, and the longer this pandemic continues, the more signs of burnout we are seeing. It's the nature of our work to show compassion, yet our work can be exhausting because of burnout and secondary trauma, which is typical in our field. In the case of severe burnout, the cure may involve taking some kind of break from your job. In contrast, secondary traumatic stress can often be addressed and successfully treated while you remain in your position or on the job.

There are differences between burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Burnout often involves work-related hopelessness and feelings of inefficacy, while secondary traumatic stress involves work-related secondary exposure to traumatically stressful events. Both share negative affect, but burnout is about being worn out, and secondary traumatic stress is about being afraid. While secondary traumatic stress may occur as a result of a single traumatic event, burnout is a process that develops over a period of time. Often secondary traumatic stress may contribute to burnout. In addition, secondary traumatic stress affects the individual team member, whereas burnout can be an individual and organizational problem. Systemic factors such as you have a poor supervisor, or you don't have a lot of resources contribute to burnout. With secondary traumatic stress, individuals have to take steps to reduce the trauma. This is where some of the self-intentional care strategies we will address later in this course come into play. With burnout symptoms, organizations can take steps to alleviate the symptoms. We'll also go through some of these strategies later in the course.

Burnout and compassionate fatigue are also slightly different because compassion fatigue involves secondary trauma and burnout. I want to define these terms further so we can identify them in our work. If you, as a therapist or a supervisor, can learn to identify and deal with each of these issues, we can minimize compassion fatigue in our environment. It's important to distinguish between burnout and compassion fatigue.

Symptoms of burnout and compassion fatigue are similar. However, the distinguishing factors include the onset of symptoms and the effect caused within the caregiver's role. In burnout, the onset is progressive and may cause indifference, disengagement, and withdrawal from clients and the work environment. Burnout is the gap between the expectation and the rewards of that work environment. Idealistic people may burn out more often than realistic people because they have higher expectations that sometimes might not be as realistic. Some strong predictors of burnout include an intrusion of work life into home life and feelings of being ineffective. Technology interruptions like email and cell phones can cause stress and burnout and decrease your control and work-life balance. The mismatch between your skills and key aspects of your job increases the risk of stress and burnout.

Compassion fatigue may be more acute in onset and may precipitate over-involvement in client care. Compassion fatigue is a state of exhaustion and dysfunction resulting from prolonged exposure to trauma or an intense event. It's biological, psychological, and social. When therapists are asked to describe their experiences of compassion fatigue in their own words, some common language I hear is that it's the wear and tear of working with traumatized clients and unhealthy and unsupported systems. The coping mechanism that is most commonly used is to disregard the overwhelming emotions that surface.

The combination of burnout and secondary traumatic stress within the context of our work can result in compassion fatigue. In our line of work, the relationships between all of these are complex, intertwined, and difficult to navigate. On top of our work environment, we have personal environments outside of work that impacts these relationships.

Contributing Factors

Compassion fatigue exists on a continuum, meaning that we may be more immune to the damaging effects at various times in our careers. At other times, we might feel very beaten down by it. Within any of our therapy settings, at any one time, there will be colleagues who are feeling well and happy and fulfilled in their work, many people who have some symptoms, and a few who feel like there's no other answer available to them but to leave the profession.

Many factors contribute to this continuum, including personal circumstances in your work situation. Current life circumstances, history, coping style, and personality style affect how compassion fatigue works through an individual and how we experience stressors and compassion fatigue. In addition to working in a challenging profession, physical therapists have other life stressors.

For example, I'm part of the sandwich generation, meaning I'm taking care of young children and my aging parents in addition to my demanding full-time job. I have a lot of life circumstances that may put me at risk of compassion fatigue. You and your colleagues are not immune to pain in your own lives. Many studies show that you may be more vulnerable to life changes like divorce and difficulties with addiction than people who do less stressful work.

Working conditions also contribute to compassion fatigue. Colleagues often say to me, "I don't have problems with my clients. In fact, I love my client work. It's really everything else at work that's grinding me down." It's clear to me that clients are not always the primary source of stress for us. It's also the paperwork, the new computerized time tracking system that we have to learn, all those documentation expectations, et cetera.

Moreover, we often spend time caring for people who may not be valued or understood in our society. I work with older adults, and often, older adults are not valued in our society. Perhaps you work with a population that is homeless or chronically ill. The working environment is often stressful and fraught with workplace negativity resulting from individual compassion fatigue and unhappiness.

Risk Factors

Personal attributes place a person more at risk for developing compassion fatigue. People who are overly conscientious or tend to be a perfectionist are more likely to suffer from compassion fatigue. Those with low levels of social support or high stress levels in their personal lives are also more likely to develop compassion fatigue. In addition, any kind of previous trauma that led to negative coping skills like bottling up or avoiding emotions, or even having those small support systems, increases the risk of developing compassion fatigue.

There are also organizational attributes that contribute to compassion fatigue. This is seen very frequently in the healthcare field and the therapy field, specifically. For example, working in a community or facility with a culture of silence where stressful events like deaths in your unit are not discussed after the events is linked to compassion fatigue. Lack of awareness of symptoms and poor training in the risks associated with high-stress jobs can also contribute to high rates of compassion fatigue.

Stages and Consequences of Compassion Fatigue

Symptoms of Compassion Fatigue

Let's go through the stages and consequences of compassion fatigue. People who experience compassion fatigue may exhibit various symptoms, including work-related, physical, and emotional symptoms. Any one of these symptoms could validate the occurrence of compassionate fatigue. However, it is important to note that more than one symptom is generally demonstrated before an employee is identified as having compassion fatigue.

Work-related symptoms include avoidance of work or dread of working with certain patients. You may use sick days frequently, so you don't have to go to work. There may be a reduced ability to feel empathy like you once did toward patients or families. There may also be a lack of joyfulness. Physical symptoms include headaches, digestive problems such as an upset stomach, muscle tension, sleep disturbances, fatigue, and cardiac symptoms like rapid heartbeats, palpitations, or chest pain or pressure. There are a lot of emotional symptoms listed below. You may not think about some of these if you are under prolonged stress.

- Mood swings

- Restlessness

- Irritability

- Oversensitivity

- Anxiety

- Excessive use of substances

- Depression

- Anger and resentment

- Loss of objectivity

- Memory issues

- Poor concentration, focus, and judgment

Assessment

An essential first step in developing an intervention plan is awareness of the problem. In addition to assessing for symptoms of compassion fatigue, a basic assessment includes collecting information regarding you or your colleagues. This information includes a description of the caregiver's work setting and working conditions, tendency to become overinvolved, and usual coping strategies and management of life crises. Also important are their usual activities to replenish themselves physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually as well as their openness to learning new skills to enhance personal and professional well-being.

Compassion Fatigue and the Employee

Many individuals who enter the field of working in therapy settings or communities with the intent to help others and provide empathetic care for clients can become victims of continuing stress of meeting the often overwhelming needs of clients and their families. This can result in compassion fatigue. It affects not only the individual in terms of job satisfaction and emotional and physical health but also the workplace environment by decreasing productivity and increasing turnover.

Phases of Compassion Fatigue

There are four distinct phases of compassion fatigue: the zealot phase, the irritability phase, the withdrawal phase, and the zombie phase. The zealot phase is often seen in new grads or someone who has just changed settings. You are motivated, ready to serve, and problem-solve. You are committed, involved, and available. You want to contribute and make a difference for your client. You're excited about your work, are volunteering for everything, and are full of energy and enthusiasm.

As time goes on, perhaps you start to cut corners. This is the irritability phase. Perhaps you start to avoid client contact, mock peers and clients, gossip or talk behind your peer's or clients' backs. You may denigrate your own efforts at wellness and lose your ability to concentrate and focus, leading to oversights and mistakes. You may start to distance yourself from others or your colleagues.

Then you move into the withdrawal phase, where you lose patience with clients, become defensive, and neglect yourself and others. You may view yourself as a victim and isolate yourself. Your clients become irritating to you, and you may start to complain about your work all the time, as well as your personal life. You feel like you are always tired and lack the energy and enthusiasm you once had.

The fourth phase is zombie, where you view others as incompetent or ignorant. You become negative and lose patience, a sense of humor, and zest for life. You start to dislike others, including your colleagues, and feel indifferent to your clients. You may anger easily.

These four phases are how compassion fatigue evolves and manifests in our everyday work. Knowing these stages is essential to identify where we are on the compassion fatigue continuum. If we don't identify compassion fatigue, we may start to feel ill or worn down or like a victim in our workplace. At times I am guilty of this type of thinking. However, when we acknowledge the symptoms of compassion fatigue and take direct action to build resiliency, we can do something about it. If we choose pathology and victimization, we start to get overwhelmed and may leave the profession or develop some type of chronic illness. On the other hand, if we choose renewal, we may become stronger, more resilient, and transformed in our careers.

Consequences of Compassion Fatigue

The consequences of compassion fatigue include increased stress, unhappiness, and medical risk. We have discussed how compassion fatigue can lead to risk within our practice. Perhaps we are making more errors due to a lack of communication or an inability to react. We might become unsympathetic and preoccupied to the detriment of our client's care. Compassion fatigue also decreases retention as the increased stress and potential trauma associated with compassion fatigue can drive clinicians away from the field. I found a study about nurses from the American Association of Colleges of Nurses that reports that 13% of newly licensed RNs work in a different career within a year after receiving their license, and 37% said they were ready to change careers. Many reported that significant ongoing emotional stress was a factor in their dissatisfaction. I couldn't find a similar study for therapists, but based on my anecdotal observations, I would say that we are experiencing the same type of turnover in therapy working environments. We are all at risk, including caregivers, therapists, and anyone exposed to prolonged stress and chronic concern.

Sources of Stress

Sources of stress include physical demands, residents living with trauma, lack of support from supervisors, and balancing life and work responsibilities. There are ethical dilemmas, client demands, and workplace tensions that can lead to lower quality of care, which, if we are not providing the care that we want to, perhaps will lower our quality of life. Continuous interaction with clients and families, and friends can foster emotions of anger, embarrassment, fear, and desperation, especially when there are no solutions to the client's problems. This can lead us to feel more frustrated or feel like things are just too complicated.

Also, perhaps we are experiencing a lack of support from colleagues or higher-ranking colleagues, or maybe there is conflict among members of the therapeutic team. Vague roles, different hierarchy ranks, or a lack of organizational structure may contribute to stress. Other factors might include individual characteristics that we discussed, such as our personality, personal experiences, emotional maturity, years of employment, family status, and ability to be actively involved in work-related decisions. These things can impact your ability to cope with stress or how much stress you experience.

Assessing Your Risk

We'll go through some tools you can use to assess your risk, but first, I want you to think about these questions.

- What are YOUR stress points?

- Are these things ongoing? Lasting for more than a few hours?

- How are you managing these stresses all day?

- Are these stressful challenges overwhelming, worrying you through the night, and affecting your daily activities and sleep?

- How are these stresses affecting your health? Your brain? Your cardiovascular system?

Assessing Compassion Fatigue and Resiliency Planning

Let's get a little more into how we use tools to plan for or assess compassion fatigue and how we plan for resiliency. Resiliency is defined as the ability to recover or adjust easily from some type of change. Some resiliency seems to be ingrained in us, but the good news is that it can also be developed and trained. We can train and condition our mental and physical reflexes and abilities for better well-being in high-compassion stress work. We should because these abilities are just as important as our technical training, and I know a lot of us are not trained in school.

Take a moment to think about which compassion fatigue symptoms you have or recognize in your life, especially those of you that identified as at risk of developing compassion fatigue.

Learning to recognize your symptoms of compassion fatigue serves a twofold purpose. It can serve as an important check-in process for a therapist who has been feeling unhappy and dissatisfied but maybe didn't have the words to explain what was happening to them. Secondly, it can allow you to develop a warning system for yourself. For example, maybe you have learned to identify compassion fatigue symptoms on a scale of one to 10. Ten is the worst you've ever felt about your work, and one is the best you've ever felt. You've learned to identify what an eight or nine looks like for you. You may know you're getting up to an eight when you don't return phone calls, or when you think about calling in sick a lot, or you can't watch any violence on TV. Maybe you know you're moving towards a five or six when you're too drained to talk to someone else or when you stop exercising. Recognizing that your level of compassion fatigue is creeping up is one of the most effective ways to implement strategies immediately before things worsen.

ProQOL - Professional Quality of Life Self-Test

Dr. Figley, who I read a quote from earlier, worked with Dr. Stamm to develop a compassion fatigue self-test called the ProQOL or the Professional Quality of Life Self-Test. This tool is a self-report measure of the positive and negative aspects of caring for others. It covers symptoms such as loss of productivity, depression, intrusive thoughts, jumpiness, tiredness, feeling on edge or trapped, and inability to separate personal and professional life. It also measures and assesses compassion satisfaction, the positive emotions associated with helping others, like happiness, pride, and satisfaction. I like this test because it's free. The 30-item self-report measure is really quick to take and looks at two subscales for burnout and secondary trauma. It's easy to use; you can give it individually or in groups, it can be given online, or you can print it out and give it the old-fashioned way with paper and pencil, and it's easy to score.

It's important to note that this test helps understand the positive and negative aspects of helping and is not considered a psychological test. It's not a medical test; it's just viewed as a screening for stress-related health problems. They share this tool pretty freely, so you can look it up on Proqol.org and then distribute it widely to your colleagues. You rank yourself on different items using a Likert scale, with one being never to five being very often.

Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS)

Another tool you can use is the secondary traumatic stress scale (STSS). This is also a self-report inventory designed to assess the frequency of secondary traumatic stress symptoms in professional caregivers. Respondents use the same Likert scale as on the ProQOL, indicating on a scale of one (never) to five (very often) how often they experienced each of the 17 secondary traumatic stress symptoms during the last week. Here are a few examples of statements from this tool.

- My heart started pounding when I thought about my work with clients.

- I had trouble sleeping.

- I felt discouraged about the future.

- I avoided people, places, or things that reminded me of my work with clients.

- I expect something bad to happen.

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)

The Maslach Burnout Inventory is a reliable measurement tool of stress and burnout. Twenty-two total items are broken up into three themes. Nine items relate to emotional exhaustion, five relate to depersonalization, and eight relate to accomplishment. The intensity scale ranges from one (never) to six (very strong). This tool is not free and must be purchased from www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory. The MBI asks you to rank statements such as I feel emotionally drained by my work, working with people all day long requires a great deal of effort, I feel like my work is breaking me down, and it stresses me too much to work in direct contact with people.

Using Psychometric Measures

If you choose to use these psychometric measures, they do have advantages and disadvantages. It's important to understand that all tests and measures look at averages in ranges, but they don't necessarily account for individual circumstances. If you or your manager use these tools as part of your clinical supervision or support, make sure they are presented as a self-assessment tool. Make sure your colleagues can opt out of sharing their specific results with you or your team if administered in a group. If your colleagues choose to share scores or specific items on scales with you, work collaboratively and respectfully with them to explore their understanding of and meanings attached to their scores.

Also, remember that high scores on compassion fatigue and burnout scales don't mean that therapists don't care for their clients or are incompetent clinicians. The scores are simply one way for you or your colleagues to understand whether you might be at risk for compassion fatigue, what you can do to prevent it, or how to address it. Viewing the combination of scores helps us "paint a picture" of what the person is telling us. These scores are simply a tool to track where you or your colleagues are on that continuum. They give us information about ourselves and allow us to understand how we're experiencing and internalizing our current therapy work environment.

It's also important to note with these scores that we're not all starting at the same place. We're all different. We have different types of education, training, socioeconomic status, and personal histories. Many of us have had obstacles overcoming our difficult lives that may include trauma. Many of us have difficult family, economic, or other personal situations that affect how we experience our current work environment.

Along those same lines, we bring our whole selves, including our past and present, to our therapy jobs. We bring our schemas and beliefs, stigma beliefs, and social support systems, both our negative and positive social support. We bring histories of trauma and illness, families, and experiences with others close to us. We also bring our economic situation to our jobs, which we saw a lot during the pandemic when we faced furloughs and layoffs.

Resiliency Planning

We often hear the term resiliency. Resiliency planning means looking holistically at the stresses and shocks that you and your colleagues are facing and working to implement creative solutions that will allow you and your colleagues to adapt and thrive, even under some of these challenging conditions that we're living in. This takes into account our individual stressors and resilience. An assessment can help plan where you put your energy into increasing that resilience, which is why we went through some of those assessments. It also includes organizational planning for resilience. We can help the organizations we work with find ways to maximize the positive aspects and reduce the negative aspects of helping individuals. With supportive supervision, assessments can be used as information for discussion. This is why we spent so much time on those today.

Resiliency Skills

There are three essential resiliency skills: self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-care. Self-awareness is being consciously attuned to your body, mind, emotions, and spirit so that you know how you are presenting at the moment. This allows you to take care of yourself and others simultaneously. This is not something that we often work on. In fact, many of us have been taught that it is virtuous to ignore or tune out what your body, emotions, and spirit are telling you. However, this is dangerous in our work. It can greatly affect our well-being and our effectiveness with others.

Knowing how tired or alert you are, how tense or relaxed you are, or how events or information coming in is impacting you are all important keys to responding in ways that will not only further your objectives and ensure the best possible outcome but help you take care of yourself now and later. Here's a quick tip. What's going on in your body, mind, and spirit when you're working is often a barometer of what's going on with your clients or your colleagues. If you're encountering resistance or feeling at a loss to understand others, you often have to check into yourself first.

The second skill is self-regulation. This is not something most of us have been taught in life. It's not highly valued in our culture because it's not as exciting or sexy as some of these other skills. However, self-regulation is very important in our work, which offers a lot of that stimulation overload all the time. Self-regulation is how we use our self-awareness to have more conscious control over our behaviors. It's about being consciously aware and in tune with our physical and emotional responses right in this moment and ongoing. This allows you to manage how you're being and presenting to others and to take care of yourself. Knowing how to instantly assess and regulate your level of awareness and arousal is important to achieving everything you're trying to in your job, but also taking care of yourself and those you're working with.

The last is self-care. We know it's important to eat right, exercise, and get enough rest, but it needs to be in ways that are sustainable and reasonably enjoyable for you. If a particular exercise program causes you more frustration or just one more overconsumption of your time and effort, then it's time to let that go and try something else. Moderation tends to be more successful and sustainable than being militant about your self-care. I know sometimes I'm a slave to my to-do list. If I have "go for a run in the morning" on my to-do list, it can become more stressful than stress relieving. We must learn how to rest our frontal lobe, get out of our executive functioning, and use other senses. Those executive functioning skills are the skills that enable us to plan, focus our tension, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks all day, every day. I think we all get a lot of practice doing this throughout our workday. For example, people often turn to nature and go outside. Many resources are behind this as being one of the most documented cures for trauma and PTSD. You want to make sure you're asking yourself questions such as:

- What brings you joy?

- When was the last time you did whatever that was?

- What gets in the way of you doing it more often?

- What are your personal triggers indicating it is time to recharge your battery?

Leading During Challenging Times

I know not everyone taking this course is a manager, so I want to spend a few moments looking at how we lead teams during difficult times. Even if you're not a leader on paper, you can lead your teammates just by recognizing how to deal with compassion fatigue during difficult situations and times.

Supervisor Guidelines for Compassion Fatigue

Because we're living and working during a pandemic, many of our colleagues are experiencing compassion fatigue. There are several ways we can address and help those colleagues. Make sure to engage in regular screening and self-assessment of compassion fatigue, address those signs and symptoms of compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress, and work with those colleagues to develop comprehensive self-care plans, re-evaluating regularly. Provide colleagues with a safe and non-judgmental environment where they can process compassion fatigue. This might be through team meetings or individual supervision. Give them a place where they can debrief stress incidents at work and support and encourage individual counseling when needed to explore any kind of that personal issues that might be contributing to compassion fatigue at work.

Trauma-Informed Supervision

One way we can approach compassion fatigue with our colleagues is by adopting a trauma-informed approach that applies to supervision. It is relationship-based supervision. Best practices for reflective supervision include regularly scheduled meetings without interruption, discussions about change management, and inviting colleagues to share experiences and explore experiences. In previous models of supervision, we've focused on things like power differentials and hierarchy, but trauma-informed supervision focuses on genuine sharing and empathetic responses and how people are bringing that into their work and their work environment. During this type of supervisory role, we would focus on mentoring, coaching, supporting professional development, building competency, and new approaches and best practices. We offer our colleagues support regarding stressors in and outside of work by helping them identify triggers for their emotional exhaustion. Our primary goal of trauma-informed supervision is to help people gain insight into their belief systems and understand how they view their clients and how this impacts their work with clients.

Trauma-informed leadership is a way of understanding or appreciating there is an emotional world of experiences within all of us. When those emotional responses are triggered in the workplace, each person responds according to the extent of their own emotional scars, traumas, and emotional strengths. Some of us may appear to be stoic and detached from emotions during conflict. Other people might have difficulty regulating, become emotionally flooded, and have difficulty negotiating their thoughts and feelings. Again, trauma-informed leadership is recognizing and honoring these emotional scars that all of your colleagues may be struggling with. It can help you, whether you're the leader or the team member, to have empathy and compassion for your colleague, which are both really powerful emotions for teammates and leaders to have.

There are a lot of benefits to trauma-informed supervision. If we have this type of support in our work environment, it will promote staff retention and reduce turnover. It can reduce levels of vicarious trauma experienced by staff. It influences the supervisee's ability to cope more effectively and have resilience. It can facilitate best practices for us and enhance worker well-being. When our colleagues and we personally experience empathy, understanding, and compassion from our supervisors or leadership teams, we feel safe, respected, and recognized. I think that plays out in how we ultimately treat ourselves as well as our clients.

Addressing Stress & Compassion Fatigue in the Workplace

We're going to look at different ways to address stress and compassion routine, starting with the workplace and then moving into how we address it in our individual lives. You may already know some of these strategies. Some will be a reminder or a refresher for you, while other strategies will be new for you. Hopefully, you can walk away with new tools to use in your everyday life and work environment. Take a moment and think about the following questions.

- Why did you choose this work?

- What do you enjoy most about your work?

- Why is it meaningful to you?

- When have you taken some action during your work day to reduce stress, enhance your effectiveness, or improve your sense of well-being?

As you experience compassion fatigue, this might be considered an inherent risk for any kind of caregiving occupation, including therapy. Job exposures may be difficult to modify as we work with chronically ill people. Interventions that promote individual resilience and education are important and likely to have significant health and economic benefits. They reduce secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and compassion fatigue and reduce the risk of more serious mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. Once you've identified your stress and compassion fatigue level, the next step is to be proactive and develop a plan for professional self-care. That means first identifying practices that are detrimental to self-care.

Amnie conducted a study in 2018 and asked 188 participants how they responded to or dealt with stress at work. The results showed that 17.6% of the people used adaptive coping focused on problem-solving. This included strategies like seeking help from a counselor or other professional stress management. The study showed that 45.2% of people used adaptive coping focused on emotional-focused coping. This includes strategies such as practicing mindfulness, meditation, and yoga, humor and jokes, and seeking higher power or religious pursuits. It also includes engaging in physical or breathing exercises and seeking social support. These are appropriate ways that we manage stress at work. The worrisome thing is this 37% of those surveyed practiced maladaptive coping styles. This was avoiding the stressful situation, withdrawing from the stressful environment, disengaging from stressful relationships, or using or abusing drugs and alcohol. This research study gives a good breakdown of how people might approach dealing with stress in the workplace.

Interventions

One intervention is to review the resources that are available in your workplace. Most work environments have an employee assistance program (EAP) as part of your HR department. The primary purpose of these programs is to provide employees with supportive counseling for personal or work-related issues. Talking about one's concerns can support the caregiver and assist with developing an action plan. I like these programs because they will present classes on relevant life-owning topics like time management, caring for an aging parent, or communicating effectively. These classes are designed to decrease stress, enhance that work-life balance, and help those who might be experiencing conditions like compassion fatigue.

We may not be able to control the current chronic uncertainty, but we can certainly share the burden. Building a community is one of the most powerful things you can do right now. Connecting with like-minded individuals is an important strategy to help prevent compassion fatigue. In addition to staying connected with your loved ones, you can set up in-person or Zoom consultation or supervision groups to check in with each other and prevent and address signs of compassion fatigue. I think the pandemic is exacerbating what was already a crisis of compassion fatigue for our therapists.

We are facing longer work hours and experiencing increased client deaths and financial fears, among other stressors. These stressors can lead to compassion fatigue. If we see signs of a colleague developing compassion fatigue, we need to check in with them. We could do simple things like texting to check in on each other's stress levels and report daily access to self-care, like taking breaks and drinking enough water to stay hydrated. It's also important that we talk about stress and normalize it. When I talk to caregivers across the board, they often tell me they didn't realize that stress is normal, so they're hesitant to ask for help. Once they realize that feeling this way is normal, individuals may be more willing to talk about their struggles and accept help.

Mentorship is also a powerful tool. Seeking out a mentor may assist in identifying strategies that will help you cope with your current work situation. This mentor may be an experienced colleague who understands the norms and expectations of your particular work environment. One example of a helpful strategy includes changing your work assignments. For example, maybe right now you are working with cardiopulmonary clients, and if you began working with neuro clients, that would change your environment. Other strategies are to recommend time off and encourage attendance at conferences. Many of our conferences are still online, so they're easier than ever to join and become a part of a particular group, organization, or conference. Become involved in a project of interest. Think about what really interests you as a therapist.

All of these actions have the potential to enhance the work environment and promote work-life balance. We have a great tool in our tool belt to modify your environment. It doesn't have to be knocking down walls. We can create comfortable, relaxing environments in our work environment right now. This can be done by transforming an available room or space into a relaxation area. Staff members can assist in selecting components of the work environment, such as soothing colors for the walls, comfortable chairs, or music that can provide comforting stress relief. I have seen facilities similar to a sensory deprivation room where you can go, which is totally quiet. It is a place you can go to for just a moment to catch your breath and regroup while you work in these stressful times.

We can also facilitate regular conferences with our colleagues to talk about some of those complex client situations. Invite all staff members to participate and address a variety of topics. Involve interdisciplinary team members to participate and talk about things such as the physical care of your clients, pain management, family dynamics, or other work-related stressors. These forums allow colleagues an opportunity to express their concerns and feelings in a safe environment and then collaboratively work to address their concerns.

Dealing with Stress During Work Hours

Many of us are very committed to our clients. We are often so busy that we can't even recognize our own needs. Self-care for therapists can be pretty complex and challenging, given that we tend to prioritize the needs of others over our own needs. Your self-care strategy has to be multifaceted and phased properly to support the sense of control and contributions that you are making without you feeling unrealistically responsible for your clients' lives.

Here are some simple things that you can do during your work shift. Make sure you monitor and pace yourself and check in with your colleagues, family, and friends. Work in partnerships or teams. Take quick stress management breaks for brief relaxation. That can be a quick two-minute break where you practice some deep breathing. Engage in helpful self-talk. Focus on things within your power, not overgeneralizing fears and thinking irrationally. Accept situations you can't change, and foster that spirit of strength and hope. We'll talk about what that looks like at the end of the course.

While there are simple things we can do to deal with stress, there are also things we want to avoid. Don't work by yourself too long without checking in with colleagues. Don't engage in self-talk such as "It's selfish to take time to rest," "Others are working around the clock, so should I," or "I could only contribute if I'm working all the time." These are not healthy sentiments and do not create overall well-being for us so that we can give the most to our clients. Avoid self-talk and attitudinal obstacles to self-care, and don't feel like you aren't doing enough. Avoid excessive intake of sweets and caffeine.

To sustain well-being at work, meet your basic needs and take breaks, as mentioned previously. Connect with colleagues and make sure you communicate clearly and in an optimistic manner. If there is some type of deficiency happening in your work environment, which happens often, make sure that you communicate constructively when correcting these deficiencies. Compliment each other. Compliments can be powerful motivators and stress moderators. Share your frustrations and solutions, but also so engage in positive problem-solving. Problem-solving is an important professional skill that often provides a feeling of accomplishment, even if we just conquer small problems. Finally, make sure to respect differences. I know I am a processor, so I must walk away and process whatever the issue is. Some people need to talk about it immediately. Make sure to recognize and respect differences in ourselves, our clients, and our colleagues.

Ensure that you honor your service. Remember that despite all the different frustrations you may be experiencing right now, you are fulfilling a noble calling and caring for those most in need. Along the same lines as what I mentioned previously, recognize your colleagues either formally or informally for their service. Make sure that you are setting boundaries on your work schedule. I have to cut myself off from checking email all night long. It can be tempting to work more, especially when we have access to so many more things online, but it can also be taxing on your health and well-being. Stick to your schedule and enforce healthy boundaries. Also, make sure that you're mindful during these uncertain times. It is tempting to stay up late mindlessly watching TV or scrolling through your smartphone, but we have to maintain a regular schedule and keep up with usual activities. We'll talk more about this when we talk about individual strategies. As we navigate this new normal, we want to consider how to use our time mindfully.

Incentives

Incentives can go a long way toward keeping therapists motivated. Again, I know not everybody is a manager taking this course. Still, I did want to quickly emphasize that a lot of nonmonetary incentives are increasingly more important than ever as a way to show that we care about our colleagues. Colleagues look for more personalized, nonmonetary incentives from their organizations. I think we're moving away from the days when monetary rewards were the only acceptable option for retaining and encouraging our colleagues. Through these rewards and motivation, we can help to attract our colleagues to our organization and help retain them in the long run. Nonmonetary incentives are easy to separate, provide emotional rewards, and are more knowledgeable and easy to talk about.

Nonmonetary incentives include time to work on individualized projects and one-on-one attention. They can be experiences like group trips to museums, a day at the spa, or anything your colleagues might like. Another reward might be mentorship for your colleagues, which we already talked about how important that could be. Maybe colleagues want to learn from the company's leaders, and getting time with those leaders would be empowering for them. Autonomy is another great incentive that we can give to our staff. Many of our colleagues love their independence, so giving them the autonomy to perform a task on their own without someone else micromanaging them is a great opportunity for your colleague.

Also, we talked about how important it is to give colleagues a chance to show appreciation for each other. Maybe one of your colleagues has gone so far out of the way that we want to recognize it with all of our coworkers. You might gather everyone's comments and then present them to that person. Other things like flexibility at work, such as offering opportunities for telecommuting or granting them an opportunity to set their work hours at work and extra PTO, are appreciated. Offering this flexibility can often help our colleagues maintain a good work-life balance. Having effective rewards and recognition programs for your colleagues can also be a great incentive tool. It can consist of sending thank you emails or handwritten notes, mentioning their success at a meeting or in front of your colleagues, recognizing them on social media, and offering colleagues opportunities to have some wellness time like volunteering. Organizing opportunities for people to go out and serve the community can boost colleagues' morale. Additional training opportunities are great nonmonetary incentives and can improve colleagues' skills and make them feel like you care about their personal growth.

Individual Strategies for Stress Management

We've talked about what we can do in the workplace, so let's move on to some more individual stress management tools. Again, I don't think any of these will be brand-new information. Still, hopefully, you can identify something that you can take away from the course and immediately incorporate it into your life to help combat or overcome compassion fatigue. Tony Robbins said, "Understanding how to find the magic moments in your daily life is critical. If you subscribe to the philosophy, 'My vacation will free me from burnout,' you're waiting a few days out of the year to make up for many days of stress. Instead, you have to be able to take mini-vacations on a daily basis."

Koinis, Giannou, and Drantaki (2015) conducted a study about coping strategies and the personal satisfaction of doctors. It was found with this group that they prefer coping strategies oriented towards direct problem management through a positive approach, reassessment, and ultimately coming up with a solution. They broke it down more specifically, which I thought was interesting. Female doctors prefer emotion-centered coping strategies, such as positive thinking or seeking help from a higher source, while male doctors usually prefer solving the problem. They looked at other stratification, like older doctors used more positive approaches and how nurses approach problem-solving. Nurses more often use problem-solving coping strategies that tend to be linked to better mental health regarding stress management at work.

This has to do with Western cultures because some studies in hospitals in the East, like Japan, Thailand, and Korea, found that nurses use emotion-centered strategies, which are also linked to good mental health. I mentioned this study to emphasize that many different strategies are available to help us cope with compassion fatigue and stress. We want to try to create that balance between caring for others and caring for ourselves.

Focus on Health

A priority for mental and physical well-being is to make sure you take daily vitamin supplements, exercise, get enough sleep, and eat healthy foods. Make and keep regular doctor appointments, and don't ignore possible symptoms of ill health. Take a break from caregiving when you need to. Respite time is crucial for us, especially right now. Schedule meditation, prayer, or quiet time each day, and keep a journal. As we've discussed, check for signs and symptoms of compassion fatigue. Find a friend to laugh with and share moments of lightness with that particular colleague.

Examine Beliefs About Self-Care

In our society, we tend to applaud people who work themselves to death and neglect their self-care to help others. We rarely applaud people for taking the day off. Therapists may have internalized this message by viewing self-care as selfish. As a result, we may not reap the benefit of any self-care efforts that we make because we engage in behaviors like worrying about work on a day off.

Simple things like playing games or watching funny movies can replenish the energy needed to help others. Even a tiny dose of positive emotion can do that. For instance, it's still pretty much winter where I live, and this morning I made sure that I noticed tiny flowers blooming when I was outside. This set the tone for the rest of the day for me. I think therapists are now experiencing the same problems their clients were experiencing, such as worrying about safety and uncertainty, financial concerns, and disrupted routines. We are usually the rocks and the river of life uncertainty for our clients, but right now, we're kind of in the river with them.

We're trying to help our clients make sense of this new reality while also doing that ourselves. It's important for caregivers to take time to reflect alone or with that trusted colleague or a therapist on any wounds that are surfacing during this uncertain time. You want to respect the fact that you're human too. Sometimes bearing witness to another person's suffering ignites things within ourselves that maybe we didn't know were there. We also need to adopt the mantra of flight attendants, so put your oxygen mask on before helping others.

Self-Care Daily Routines

Good self-care means developing a routine that makes each day predictable. It should include the big five of self-care: adequate sleep, healthy nutrition, physical activity, relaxation, and socializing. The schedule should also include five minutes for self-check-in each morning to assess body tension and mental worries.

Individual Stress Management

To manage individual stress, use practical ways to cope and relax. Relax your body often by doing things that work for you. This might be taking deep breaths, stretching, or engaging in activities you enjoy. Make sure to pace yourself between stressful activities. I tend to structure my days so I do an arduous task, and then I do an easier, hard, and easier task. Make sure to talk about your experiences and feelings with loved ones and friends if you find that helpful. Maintain a sense of hope and positive thinking. I keep a journal where I write down things I'm grateful for and things that are going well in my life. When I start to feel a little hopeless, I will take out that journal and review some of the things that helped me maintain that sense of positive coping strategies.

Stress Busting Foods

As I mentioned previously, healthy nutrition is essential in stress management. Eating healthy, well-balanced meals is vital, but some foods help reduce stress.

- Complex carbs

- Oranges

- Spinach

- Fatty fish

- Black tea

- Pistachios

- Avocados

- Almonds

- Raw veggies

- Milk

We all know oranges have a lot of vitamin C, but studies suggest that vitamin C can curb the levels of stress hormones while strengthening the immune system. In one of these studies, people with high blood pressure and higher cortisol levels returned to normal more quickly when they took vitamin C before some type of stressful task. Spinach is a source of magnesium, which can be a trigger for things like headaches and fatigue. If you're taking too little magnesium or have too little magnesium in your diet, you may develop headaches and fatigue, which might compound the effects of stress. Spinach and other green leafy vegetables can help you stock back up on your magnesium. Avocados reduce high blood pressure and are full of potassium. Half an avocado has more potassium than a medium size banana. Try reaching for an avocado if you have stress-related cravings and want a high-fat treat. Almonds are full of vitamin E to boost your immune system and vitamin B to make you more resilient during stress, depression, or periods of exacerbation of stress or depression.

Hydration is Critical

We also know water is critical, but I want to share some research behind that. A study at the University of Connecticut showed that even mild dehydration could cause mood problems. By the time you feel thirsty, it's often too late as our thirst sensation doesn't appear until we're already about 2% dehydrated. By then, dehydration has already set in and is starting to impact how our mind and body perform.

Movement is Powerful

Everyone knows that movement is powerful. Hippocrates once said, "If you're in a bad mood, go for a walk and if you're still in a bad mood, go for another walk." Physical activity can help lower overall stress levels and improve quality of life (mentally & physically). You pump up endorphins when you exercise, which helps you feel good. For example, after you play tennis or swim in the pool, you'll often find that you've forgotten the day's irritation. Exercising regularly can relieve the tension, anxiety, anger, and mild depression that often go hand-in-hand with stress. It can improve the quality of sleep, which can be negatively impacted by stress, depression, and anxiety.

Keep Your Immune System Strong

It's important to keep your immune system strong to stay strong and healthy for ourselves and our clients. Below are things you are likely already doing.

- Washing your hands

- Get enough sleep

- Eat well and stay hydrated

- Take vitamins and any prescriptions

- Prioritize personal hygiene and limit contact with others

- Cover your cough or sneeze

- Disinfect with anti-bacterial wipes

- Avoid touching your face, eyes, nose, and mouth

- Stay home when you are sick

- Exercise and stay active

- Get fresh air

Sleep

I will spend a moment on sleep because I think sleep is often underrated as a powerful tool. If we interrupt our sleep cycles, it can have some profound negative health and safety consequences, including impaired immune function and increased accidents and errors at work. You can take steps to make sure that you are getting healthy sleep. In addition to making sleep a priority, get at least 15 to 60 minutes of bright light upon waking. Natural sunlight is best. Going outside for a few minutes is better to get some sunlight and fresh air. Exercise closer to your wake time to help with your circadian rhythm. It can signal day time has begun and, as a result, improve your sleep quality. I can't exercise close to bedtime because it tends to amp me up. That's part of my sleep hygiene, and I'm aware of it, so I ensure I pay attention throughout the day.